| w | statement | H / L | r | RC ? |

| 0.80 | When I was learning to read at school, I often felt I was slower than others in my class | H | 0.51 | - |

| 0.53 | My spelling is generally very good | L | - 0.52 | RC |

| 0.70 | I find it very challenging to manage my time efficiently | H | 0.13 | - |

| 0.71 | I can explain things to people much more easily verbally than in my writing | H | 0.60 | - |

| 0.57 | I think I am a highly organized learner | L | - 0.08 | - |

| 0.48 | In my writing I frequently use the wrong word for my intended meaning | H | 0.67 | - |

| 0.36 | I generally remember appointments and arrive on time | L | 0.15 | - |

| 0.75 | When I'm reading, I sometimes read the same line again or miss out a line altogether | H | 0.41 | - |

| 0.76 | I have difficulty putting my writing ideas into a sensible order | H | 0.51 | - |

| 0.80 | In my writing at school, I often mixed up similar letters like 'b' and 'd' or 'p' and 'q' | H | 0.61 | - |

| 0.57 | When I'm planning my work I use diagrams or mindmaps rather than lists or bullet points | neutral | 0.49 | - |

| 0.75 | I'm hopeless at remembering things like telephone numbers | H | 0.41 | - |

| 0.52 | I find following directions to get to places quite straightforward | L | -0.04 | - |

| 0.57 | I prefer looking at the 'big picture' rather than focusing on the details | neutral | 0.21 | - |

| 0.63 | My friends say I often think in unusual or creative ways to solve problems | H | 0.20 | - |

| 0.52 | I find it really challenging to make sense of a list of instructions | H | 0.49 | - |

| 0.52 | I get my 'lefts' and 'rights' easily mixed up | H | 0.39 | - |

| 0.70 | My tutors often tell me that my essays or assignments are confusing to read | H | 0.36 | - |

| 0.64 | I get in a muddle when I'm searching for learning resources or information | H | 0.57 | - |

| 0.72 | I get really anxious if I'm asked to read 'out loud' | H | 0.36 | - |

discourse study-blog | resources | lit review maps | profiles

enquiry research QNR | dysdefs QNR | dysdims QNR

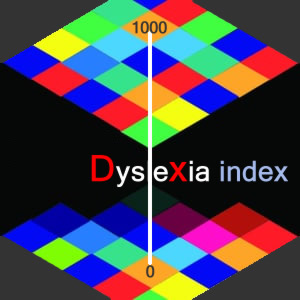

dyslexia index

dyslexia index Dyslexia Index - designing a self-report profiler that identifies dyslexia-like study attributes in university students

Dyslexia Index - designing a self-report profiler that identifies dyslexia-like study attributes in university students

- Introduction

- Dyslexia - a complex phenomenon

- Labels, categories, dilemmas of difference and inclusivityk

- Measuring dyslexia - "how dyslexic am I?"

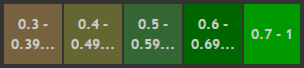

- Dyslexia Index (Dx)

- Construction of the Dyslexia Index (Dx) Profiler

- Feeding these results into the construction of the Dx Profiler

- Reverse coding data

- Internal Consistency Reliability - Cronbach's α

- Main research preliminary findings

- Relating Dyslexia Index (Dx) to Academic Behavioural Confidence (ABC)

- Concluding remarks

- References

INTRODUCTION

This paper presents detail of the design and development of the Dyslexia Index Profiler which featured as an integral part of the main research questionnaire for this project, recently deployed to university students to collect primary data for addressing the project's research questions.

Some theoretical perspectives about dyslexia and about issues of accommodating individual learning differences in university contexts form the opening sections. This is followed by a detailed description of the design and development of the Dyslexia Index Profiler, the background research that has been undertaken to try to bring a fresh perspective on the difficult issue of identifying dyslexia amongst university students which includes a report of two early-stage, small-scale enquiries undertaken to inform that design and development.

Following this, a report on the statistical processes that have been utilized to attempt to validate the profiler is presented, which includes a brief review of the literature relating to issues surrounding Likert scale questionnaire design. The paper concludes with an outline of the immediate plans for the continuation of the overall research project together with an indication about how the Dyslexia Index Profiler has already been modified in the light of the data analysis.

DYSLEXIA - A COMPLEX PHENOMENON

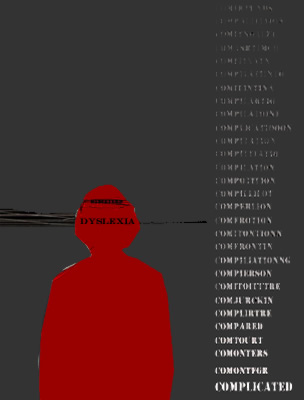

Dyslexia - whatever it is - is complicated.

There is a persistent range of research methodologies and a compounding variety of interpretations that seek to explain dyslexia which continue to be problematic (Rice & Brooks, 2004) and so attributing any accurate, shared meaning to the dyslexic label that is helpful rather than confusing is challenging.

Theories of developmental dyslexia differ quite widely, especially when it comes down to interpreting causes for the variety of characteristics that can be presented (Ramus, 2004). Well over a century of research, postulation, commentary, narrative and theory has consistently failed to arrive at an end-point definition to the dyslexia label (Smythe, 2011), and as long as positive learning outcomes based on high levels of literacy remain connected to 'intellect' (MacDonald, 2009), learning barriers attributable to even a social construction of dyslexia are likely to remain, no matter how the syndrome is defined (Cameron & Billington, 2015).

Dyslexia - whatever it is - is complicated.

There is a persistent range of research methodologies and a compounding variety of interpretations that seek to explain dyslexia which continue to be problematic (Rice & Brooks, 2004) and so attributing any accurate, shared meaning to the dyslexic label that is helpful rather than confusing is challenging.

Theories of developmental dyslexia differ quite widely, especially when it comes down to interpreting causes for the variety of characteristics that can be presented (Ramus, 2004). Well over a century of research, postulation, commentary, narrative and theory has consistently failed to arrive at an end-point definition to the dyslexia label (Smythe, 2011), and as long as positive learning outcomes based on high levels of literacy remain connected to 'intellect' (MacDonald, 2009), learning barriers attributable to even a social construction of dyslexia are likely to remain, no matter how the syndrome is defined (Cameron & Billington, 2015).

Some definition perspectives

Frith (1999) tried to get to the heart of the definition problem by exploring three levels of description - behavioural, cognitive and biological - but still defined dyslexia as a neuro-biological disorder, which discussed controversial hypothetical deficits and how these impact on the clinical presentation of dyslexia. Despite an attempt to provide a targeted explanation through an analysis of the multifactoral impact of these three levels, this paper still broadly concluded that 'undiagnosable' cultural and social factors together with (at the time) uncomprehended genetically-derived 'brain differences' obfuscate a definitive conclusion. Ramus (2004) took Frith's framework further, firstly by drawing our attention to the diversity of 'symptoms' and argued that neurobiological differences are indeed at the root of phonological processing issues which are characteristic indicators of a dyslexic learning difference (Vellutino et al, 2004). But more so, his study shed early light on these variances as an explanation for the apparent comorbidity of dyslexia with other neurodevelopmental disorders, often presented as sensory difficulties in many domains, for example, visual, motor control and balance, and others, which adds to the challenges in pinning dyslexia down. Although Ramus does not propose a single, new neurobiological model for dyslexia, more so suggests a blending of the existing phonological and magno-cellular theories (see below) into something altogether more cohesive, the claim is that evidence presented is consistent with results from studies in both research domains to date, and so is quite weighty.

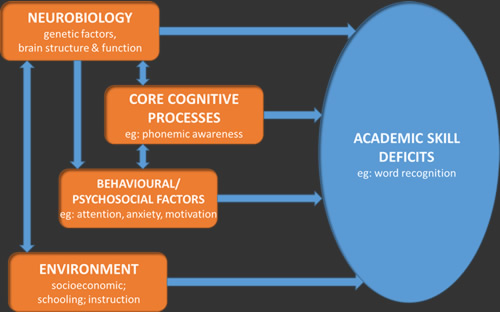

Fletcher (2009), in trying to bring together a summary of more recent scientific understanding of dyslexia, attempts to visualize the competing/contributory factors that can constitute a dyslexic profile in a summary diagram (below) which is helpful. Fletcher adds a dimension to those previously identified by Frith, Ramus, et al by factoring in environmental influences, not the least of which includes social aspects of learning environments, which are likely to be the most impacting factor on learning identity. Mortimore & Crozier (2006) demonstrated that acceptance of dyslexia as part of their learning identity was often something that students new to university were unwilling to embrace, not the least because they felt that the 'fresh start' of a tertiary educational opportunity would enable them to adopt other more acceptable social-learning identities that were deemed more inviting.

Fletcher (2009), in trying to bring together a summary of more recent scientific understanding of dyslexia, attempts to visualize the competing/contributory factors that can constitute a dyslexic profile in a summary diagram (below) which is helpful. Fletcher adds a dimension to those previously identified by Frith, Ramus, et al by factoring in environmental influences, not the least of which includes social aspects of learning environments, which are likely to be the most impacting factor on learning identity. Mortimore & Crozier (2006) demonstrated that acceptance of dyslexia as part of their learning identity was often something that students new to university were unwilling to embrace, not the least because they felt that the 'fresh start' of a tertiary educational opportunity would enable them to adopt other more acceptable social-learning identities that were deemed more inviting.

One respondent in the current research being partially reported in this paper provided this related, sobering reflection:

- "I don't really like feeling different because people start treating you differently. If they know you have dyslexia, they normally don't want to work with you because of this ... I am surprised I got into university and I am where I am ... and I find it very hard [so] I don't speak in class in case I get [questions] wrong and people laugh" (respondent #85897154, available here)

This highlights aspects of dyslexia which impact on the identity of the individual in ways that mark them as different, in learning contexts at least, and is an element that will be discussed below.

Other explanations rooted in physiology, notably genetics, have encouraged some further interest, notably a paper by Galaburda et al (2006) who claimed to have identified four genes linked to developmental dyslexia following research with rodents, and a more recent study which was concerned with identifying 'risk genes' in genetic architecture (Carion-Castillo et al, 2013). However, scientific as these studies may have been, their conclusions serve as much to prolong the controversy about how to define dyslexia rather than clarify what dyslexia is because these studies add yet another dimension to the dyslexia debate.

Sensory differences is an explanation that has attracted support from time to time and attributes the manifestations of dyslexia most especially to visual differences - the magnocellular approach to defining dyslexia (Evans, 2003 amongst many others). Whilst there is no doubt that for many, visual stress can impair access to print, this scotopic sensitivity, more specifically referred to as Meares-Irlen Syndrome (MIS), may be a good example of a distinct but co-morbid condition that sometimes occurs alongside dyslexia rather than is an indicator of dyslexia. Later research by Evans & Kriss (2005) accepted this comorbidity idea and found that there was only a slightly higher prevalence of MIS in the individuals with dyslexia in their study in comparison to their control. Common in educational contexts to ameliorate vision differences, especially in universities, there is a long-standing recommendation for tinted colour overlays to be placed on hard-copy text documents, or assistive technologies that create a similar effect for electronic presentation of text. But evidence that this solution for remediating visual stress is more useful for those with dyslexia than for everyone else is sparse or contrary (eg: Henderson et al, 2013) or as one study found, can actually be detrimental to reading fluency, particularly in adults (Denton & Meindl, 2016). So although the relationship between dyslexia and visual stress remains unclear, there is evidence to indicate that there is an interaction between the two conditions which may have an impact on the remediation of either (Singleton &Trotter, 2005).

Sensory differences is an explanation that has attracted support from time to time and attributes the manifestations of dyslexia most especially to visual differences - the magnocellular approach to defining dyslexia (Evans, 2003 amongst many others). Whilst there is no doubt that for many, visual stress can impair access to print, this scotopic sensitivity, more specifically referred to as Meares-Irlen Syndrome (MIS), may be a good example of a distinct but co-morbid condition that sometimes occurs alongside dyslexia rather than is an indicator of dyslexia. Later research by Evans & Kriss (2005) accepted this comorbidity idea and found that there was only a slightly higher prevalence of MIS in the individuals with dyslexia in their study in comparison to their control. Common in educational contexts to ameliorate vision differences, especially in universities, there is a long-standing recommendation for tinted colour overlays to be placed on hard-copy text documents, or assistive technologies that create a similar effect for electronic presentation of text. But evidence that this solution for remediating visual stress is more useful for those with dyslexia than for everyone else is sparse or contrary (eg: Henderson et al, 2013) or as one study found, can actually be detrimental to reading fluency, particularly in adults (Denton & Meindl, 2016). So although the relationship between dyslexia and visual stress remains unclear, there is evidence to indicate that there is an interaction between the two conditions which may have an impact on the remediation of either (Singleton &Trotter, 2005).

An alternative viewpoint about the nature of dyslexia is represented by a significant body of researchers who take a strong position based on the notion of 'neuro-diversity'. The BRIAN.HE project (2005), now being revised but with many web resources still active and available, hailed learning differences as a natural consequence of human diversity. Pollak's considerable contribution to this thesis about dyslexia, both through the establishment of BRIAN.HE and notably drawn together in a collection of significant papers (Pollak, 2009), expounds the idea that dyslexia is amongst so-called 'conditions' on a spectrum of neuro-diversity which includes, for example, ADHD and Asperger's Syndrome. Particularly this view supports the argument that individuals with atypical brain 'wiring' are merely at a different place on this spectrum in relation to those others who are supposedly more 'neurotypical'. The greater point here is elegantly put by Cooper (2006), drawing on the social-interactive model of Herrington & Hunter-Carch (2001), and this is the idea that we are all neurodiverse and that it remains society's intolerance to differences that conceptualizes 'neurotypical' as in the majority. This may be particularly apparent in learning contexts where delivering the curriculum through a largely inflexible literacy-based system discriminates against particular presentations of neurodiversity (eg: Cooper, 2009).

The final thesis will present a more detailed review of the various standpoints on what dyslexia is, and especially what it means to be dyslexic based on the evidence from those labelled as such. Additionally, the final thesis will also contain a detailed report on a preliminary enquiry addressed to dyslexia support tutors engaged in universities which was designed to explore their viewpoints on dyslexia. This enquiry was more of a 'straw poll' than a scientific study from which it was merely intended to gain an overview of the current understanding of dyslexia amongst professionals working in their domains of functioning. The enquiry requested participants to create a meritocratic list of definitions of dyslexia from choices provided in a basic questionnaire. Although only 30 responses were received, they represented a broad cross-section of professional colleagues working with students with dyslexia with the results presenting an interesting snapshot of dyslexia in the contemporary context. A preliminary report about this enquiry is available on the project webpages and later on, a deeper analysis of these results obtained will be connected with additional data gathered from students in the main research questionnaire which requested information about how students learned about their dyslexia (reported more fully below). In this way it is hoped insights might be gained on aspects of the impact of the identification process and this will be presented within the final thesis.

So defining dyslexia as a starting point for an investigation is challenging. This causes problems for the researcher because the focus of the study ought to be supported by a common understanding about what dyslexia means because without this, it might be argued that the research outcomes are relational and definition-dependent rather than absolute. However, given the continued controversy about the nature of dyslexia, it is necessary to work within this relatively irresolute framework and nevertheless locate the research and the results and conclusions of the research accordingly.

What seems clear and does seem to meet with general agreement, is that at school-age level, difficulties experienced in phonological processing and the 'normal' development of word recognition automaticity appear to be the root causes of the slow uptake of reading skills and associated challenges with spelling. Whether this is caused by a dyslexia of some description or is simply unexplained poor reading may be difficult to determine. Setting all other variables aside, a skilful teacher or parent will notice that some children find learning to read particularly challenging and this will flag up the possibility that these learners are experiencing a dyslexia.

What also seems clear, is that for learners of above average academic ability but who indicate dyslexia-associated learning challenges - in whatever way both of these attributes are measured - it is reasonable to expect these learners to strive to extend their education to post-secondary levels along with everyone else in their academic peer groups, despite the learning challenges that they face as a result of their learning differences. Amongst many other reasons which include desire for improved economic opportunities resulting from success at university, one significant attraction of higher education is a desire to prove self-worth (Madriaga, 2009). An analysis of HESA data bears out the recent surge in participation rates amongst traditionally under-represented groups at university of which students with disabilities form one significant group (Beauchamp-Prior, 2013). There is plenty of recent research evidence to support this which relates to students entering university with a previously identified learning difference and this will be discussed more fully in the final thesis. But a compounding factor which suggests an even greater prevalence of dyslexia at university beyond data about dyslexic students on entry is indicated through the rising awareness of late-identified dyslexia at university. This is evidenced not the least through interest in creating screening tools such as the DAST (Dyslexia Adult Screening Test, Fawcett & Nicholson, 1998) and the LADS software package (Singleton & Thomas, 2002) to name just two technology-based items which will be discussed further, below. But this is also a measure of the recurring need to develop and refine a screening tool that works at university level which takes more interest in the other learning challenges as additional identifying criteria rather than persist with assessing largely literacy-based skills and the relationship of these to perhaps, speciously-defined, measures of 'intelligence'. This is also discussed a little more and in the context of this paper, below.

Disability, deficit, difficulty or difference?

With the exception of Cooper's description of dyslexia being an example of neuro-diversity rather than a disability, difficulty or even difference, definitions used by researchers and even professional associations by and large remain fixed on the issues, challenges and difficulties that dyslexia presents when engaging with the learning that is delivered through conventional curriculum processes. This approach compounds, or certainly tacitly compounds the 'adjustment' agenda which is focused on the learner rather than the learning environment.

'Difficulty' or 'disorder' are both loaded with negative connotations that imply deficit, particularly within the framework of traditional human learning experiences in curriculum delivery environments that do remain almost entirely 'text-based'. This is despite the last decade or two of very rapid development of alternative, technology or media-based delivery platforms that have permeated western democracies and much of the alternative and developing worlds. This 'new way' is embraced by an information society that sees news, advertising, entertainment and 'gaming', government and infrastructure services, almost all aspects of human interaction with information being delivered through electronic mediums. And yet formal processes of education by and large remain steadfastly text-based which, although now broadly delivered electronically, still demand a 'conventional' ability to properly and effectively engage with the 'printed word' both to consume knowledge and also to create it. This persistently puts learners with dyslexia - in the broadest context - and with dyslexia-like learning profiles at a continual disadvantage and hence is inherently unjust. An interesting, forward-looking paper by Cavanagh (2013) succinctly highlights this tardiness in the delivery of education and learning to keep up with developments in information diversity and candidly observes that the collective field of pedagogy and andragogy should recognize that, rather than learners, it is curricula that is disabled and hence, needs be fixed – a standpoint that resonates with the underlying rationale that drives this PhD Project.

'Difficulty' or 'disorder' are both loaded with negative connotations that imply deficit, particularly within the framework of traditional human learning experiences in curriculum delivery environments that do remain almost entirely 'text-based'. This is despite the last decade or two of very rapid development of alternative, technology or media-based delivery platforms that have permeated western democracies and much of the alternative and developing worlds. This 'new way' is embraced by an information society that sees news, advertising, entertainment and 'gaming', government and infrastructure services, almost all aspects of human interaction with information being delivered through electronic mediums. And yet formal processes of education by and large remain steadfastly text-based which, although now broadly delivered electronically, still demand a 'conventional' ability to properly and effectively engage with the 'printed word' both to consume knowledge and also to create it. This persistently puts learners with dyslexia - in the broadest context - and with dyslexia-like learning profiles at a continual disadvantage and hence is inherently unjust. An interesting, forward-looking paper by Cavanagh (2013) succinctly highlights this tardiness in the delivery of education and learning to keep up with developments in information diversity and candidly observes that the collective field of pedagogy and andragogy should recognize that, rather than learners, it is curricula that is disabled and hence, needs be fixed – a standpoint that resonates with the underlying rationale that drives this PhD Project.

Cavanagh is one of the more recent proponents of a forward-facing, inclusive vision of a barrier-free learning environment - the Universal Design for Learning (UDL) – which as a 20-year-old 'movement' originating from a seminal paper by Rose & Meyer (2000) is attempting to tackle this issue in ways that would declare dyslexia to be much more widely recognized as, at worst, a learning difference amongst a plethora of others, rather than a learning difficulty or worse, disability. With its roots in the domain of architecture and universal accessibility to buildings and structures, the core focus of UDL is that the learning requirements of all learners are factored into curriculum development and delivery so that every student's range of skills, talents, competencies and challenges are recognized and accommodated without recourse to any kind of differentiated treatment to 'make allowances'. Hence it becomes the norm for learning environments to be much more easily adaptable to learners' needs rather than the other way around. This will ultimately mean that text-related issues, difficulties and challenges that are undoubted deficits in conventional learning systems cease to have much impact in a UDL environment. There is an increasing body of evidence to support this revolution in designing learning in this way, where researchers persistently draw attention to the learning-environment challenges facing different learners, ranging from equitable accommodation into the exciting new emphasis on developing STEM education (eg: Basham & Marino, 2013) to designing learning processes for properly including all students into health professions courses (eg: Heelan, et al, 2015).

However until this revolution is complete, other measures are still required to ensure an element of equitability in learning systems that fail to properly recognize and accommodate learning diversity.

LABELS, CATEGORIES, DILEMMAS OF DIFFERENCE AND INCLUSIVITY

There are many well-rehearsed arguments that have sought to justify the categorization of learners as a convenient exercise in expediency that is generally justified as essential for establishing rights to differentiated 'support' as the most efficacious forms of intervention (Elliott & Gibbs, 2008). This is support which aims to shoe-horn a learner labelled with 'special needs' into a conventional learning box, by means of the application of 'reasonable adjustments' as remediative processes to compensate for learning challenges apparently attributed to their disability.

There are many well-rehearsed arguments that have sought to justify the categorization of learners as a convenient exercise in expediency that is generally justified as essential for establishing rights to differentiated 'support' as the most efficacious forms of intervention (Elliott & Gibbs, 2008). This is support which aims to shoe-horn a learner labelled with 'special needs' into a conventional learning box, by means of the application of 'reasonable adjustments' as remediative processes to compensate for learning challenges apparently attributed to their disability.

Outwardly, this is neat, usually well-meaning, ticks boxes, appears to match learner-need to institutional provision, and apparently 'fixes' the learner in such a way as to level the academic playing field so as to reasonably expect such learners to 'perform' in a fair and comparable way with their peers. Richardson (2009) reported on analysis of datasets provided by HESA that this appears to work for most categories of disabled learners in higher education, also demonstrating that where some groups did appear to be under-performing, this was due to confounding factors that were unrelated to their disabilities.

However some researchers claim that such accommodations can sometimes positively discriminate, leading to unfair academic advantage because the 'reasonable adjustments' that are made are somewhat arbitrarily determined and lack scientific justification (Williams & Ceci, 1999). Additionally, there is an interesting concern that many students who present similar difficulties and challenges when tackling their studies to their learning-disabled peers but who are not officially documented through a process of assessment or identification (that is, diagnosis) are unfairly denied similar access to corresponding levels of enhanced study support. It is exactly this unidentified learning difference that the metric in this research study is attempting to reveal and the development of which is described in detail below. Anecdotal evidence from this researcher's own experience as an academic guide in higher education suggests that at university, many students with learning differences such as dyslexia have no inkling of the fact, which is supported by evidence (for example) from a survey conducted in the late 90s which reported that 43% of dyslexic students at university were only identified after they have started their courses (National Working Party on Dyslexia in HE, 1999).  Indeed it has also been reported that some students, witnessing their friends and peers in possession of newly-provided laptops, study-skills support tutorials and extra time to complete their exams all provided through support funding, go to some lengths to feign difficulties in order to gain what they perceive to be an equivalent-to-their-friends, but better-than-equal academic advantage over others not deemed smart enough to play the system (Harrison et al, 2008, Lindstrom et al, 2011).

Indeed it has also been reported that some students, witnessing their friends and peers in possession of newly-provided laptops, study-skills support tutorials and extra time to complete their exams all provided through support funding, go to some lengths to feign difficulties in order to gain what they perceive to be an equivalent-to-their-friends, but better-than-equal academic advantage over others not deemed smart enough to play the system (Harrison et al, 2008, Lindstrom et al, 2011).

But there is some argument to suggest that, contrary to dyslexia being associated with persistent failure (Tanner, 2009), attaching the label of dyslexia to a learner - whatever dyslexia is - can be an enabling and empowering process at university exactly because it opens access to support and additional aids, especially technology which has been reported to have a significantly positive impact on study (Draffan et al, 2007). Some researchers who investigated the psychosocial impacts of being designated as dyslexic have demonstrated that embracing their dyslexia enabled such individuals to identify and use many personal strengths in striving for success, in whatever field (Nalavany et al, 2011). In taking the neurodiversity approach however, Grant (2009) points out that neurocognitive profiles are complicated and that the identification of a specific learning difference might inadvertently be obfuscated by a diagnostic label, citing dyslexia and dyspraxia as being very different situations but which share many similarities at the neurocognitive level. Ho (2004) argued that despite the 'learning disability' label being a prerequisite for access to differentiated provision in learning environments and indeed, civil rights protections, these directives and legislations have typically provided a highly expedient route for officialdom to adopt the medical model of learning disabilities and pay less attention or even ignore completely other challenges in educational systems. 'Learning disabilities' (LD) is the term generally adopted in the US, broadly equivalent to 'learning difficulties' everywhere else, of which it is generally agreed that 'dyslexia' forms the largest subgroup; and the legislation that is relevant here is enshrined in the UK in the Disability Discrimination Act, later followed by the Disability Equality Duty applied across public sector organizations which included places of learning, all replaced by the Equality Act 2010 and the Public Sector Equality Duty 2011. So one conclusion that may be drawn here is that as long as schools, and subsequently universities persist in relying heavily on reading to impart and subsequently to gain knowledge, and require writing to be the principal medium for learners to express their ideas and hence for their learning to be assessed, pathologizing the poor performance of some groups of learners enables institutions to avoid examining their own failures (Channock, 2007).

Other arguments focus on stigmatization associated with 'difference':

On the disability agenda, many studies examine the relationship between disability and stigma with several drawing on social identity theory. For example, Nario-Redmond et al (2012) in a study about disability identification outlined that individuals may cope with stigma by applying strategies that seek to minimize stigmatized attributes but that often this is accompanied by active membership of stigmatized groups in order to enjoy the benefit of collective strategies as a means of self-protection. Social stigma itself can be disabling and the social stigma attached to disability, not least given a history of oppression and unequal access to many, if not most of society's regimens, is particularly so. Specifically in an education context, there is not necessarily a connection between labels of so-called impairment and the categorization of those who require additional or different provision (Norwich, 1999). Indeed, there is a significant body of research that identifies disadvantages in all walks of life that result from the stigmatization of disabilities (eg: McLaughlin, et al, 2004, Morris & Turnbill, 2007, Trammel, 2009). Even in educational contexts and when the term is arguably softened to 'difficulties' or even more so to 'differences', the picture remains far from clear with one study (Riddick, 2000) suggesting that stigmatization may already exist in advance of labelling, or even in the absence of labelling at all. Sometimes the stigma is more associated with the additional, and sometimes highly visible, learning support - students accompanied by note-takers for example - designed to ameliorate some learning challenges (Mortimore, 2013) with some studies reporting a measurable social bias against individuals with learning disabilities who were perceived less favourably than their non-disabled peers (eg: Tanner, 2009, Valas, 1999,). This was not the least also evidenced from the qualitative data that has been collected in this current research project which will be more deeply analysed later, however an example presented here is representative of many similar others that were received:

Other arguments focus on stigmatization associated with 'difference':

On the disability agenda, many studies examine the relationship between disability and stigma with several drawing on social identity theory. For example, Nario-Redmond et al (2012) in a study about disability identification outlined that individuals may cope with stigma by applying strategies that seek to minimize stigmatized attributes but that often this is accompanied by active membership of stigmatized groups in order to enjoy the benefit of collective strategies as a means of self-protection. Social stigma itself can be disabling and the social stigma attached to disability, not least given a history of oppression and unequal access to many, if not most of society's regimens, is particularly so. Specifically in an education context, there is not necessarily a connection between labels of so-called impairment and the categorization of those who require additional or different provision (Norwich, 1999). Indeed, there is a significant body of research that identifies disadvantages in all walks of life that result from the stigmatization of disabilities (eg: McLaughlin, et al, 2004, Morris & Turnbill, 2007, Trammel, 2009). Even in educational contexts and when the term is arguably softened to 'difficulties' or even more so to 'differences', the picture remains far from clear with one study (Riddick, 2000) suggesting that stigmatization may already exist in advance of labelling, or even in the absence of labelling at all. Sometimes the stigma is more associated with the additional, and sometimes highly visible, learning support - students accompanied by note-takers for example - designed to ameliorate some learning challenges (Mortimore, 2013) with some studies reporting a measurable social bias against individuals with learning disabilities who were perceived less favourably than their non-disabled peers (eg: Tanner, 2009, Valas, 1999,). This was not the least also evidenced from the qualitative data that has been collected in this current research project which will be more deeply analysed later, however an example presented here is representative of many similar others that were received:

- "When I was at school I was told that I had dyslexia. When I told them I wanted to be a nurse [and go to university], they laughed at me and said I would not achieve this and would be better off getting a job in a supermarket" (respondent #48997796, available here)

Similar evidence relating to social bias was recorded by Morris & Turnbill (2007) through their study exploring the disclosure of dyslexia in cohorts of students who successfully made it to university to train as nurses, although it is possible that their similar conclusions to these other studies were confounded by nurses' awareness of workplace regulations relating to fitness to practice. This aspect of disclosure-reluctance has been mentioned earlier. It has also been recorded that the dyslexia (LD) label might even produce a differential perception of future life success and other attributes such as attractiveness or emotional stability despite such a label presenting no indication whatsoever about any of these attributes or characteristics (Lisle & Wade, 2014). Perhaps the most concerning, is evidence that parents and especially teachers may have lower academic expectations of young people attributed with learning disabilities or dyslexia based on a perceived predictive notion attached to the label (Shifrer, 2013, Hornstra et al, 2014) and that in some cases, institutional processes have been reported to significantly contribute to students labelled as 'learning-disabled' choosing study options broadly perceived to be less academic (Shifrer et al, 2013).

As a key researcher and commentator of many years standing, Stanovich has written extensively on dyslexia, on inclusivity and the impact of the labelling of differences. His approach appears to be principally two-fold. Firstly to fuel the debate about whether dyslexia per se exists, a viewpoint that has emerged from the research and scientific difficulties that he claims arise from attempts to differentiate dyslexia from other poor literacy skills; and secondly that given that dyslexia in some definition or another is a quantifiable characteristic, argues strongly that as long as the learning disability agenda remains attached to aptitude-achievement discrepancy measurement and fails to be a bit more self-critical about its own claims, (Stanovich, 1999), its home in the field of research will advance only slowly. Indeed a short time later he described the learning disabilities field as 'not ... on a scientific footing and continu[ing] to operate on the borders of pseudoscience' (Stanovich, 2005, p103). His position therefore fiercely advocates a more inclusive definition of learning disabilities as being one which effectively discards the term entirely because it is 'redundant and semantically confusing' (op cit, p350) a persistent argument that others echo. Lauchlan & Boyle (2007) broadly question the use of labels in special education, concluding that aside from being necessary in order to gain access for support and funding related to disability legislation, the negative effects on the individual can be considerable and may include stigmatization, bullying, reduced opportunities in life and perhaps more significantly, lowered expectations about what a 'labelled' individual can achieve (ibid, p41) as also reported above. Norwich (1999, 2008, 2010) has written extensively about the connotations of labelling, persistently arguing for a cleaner understanding of differences in educational contexts because labels are all too frequently stigmatizing and themselves disabling, referring to the 'dilemma of difference' in relation to arguments 'for' and 'against' curriculum commonality/differentiation for best meeting the educational needs of differently-abled learners. Armstrong & Humphrey (2008) suggest a 'resistance-accommodation' model to explain psychological reactions to a 'formal' identification of dyslexia, the 'resistance' side of which is typically characterized by a disinclination to absorb the idea of dyslexia into the self-concept, possibly resulting from perhaps more often, negatively vicarious experiences of the stigmatization attached to 'difference', whereas the 'accommodation' side is suggested to take a broadly positive view by making a greater effort to focus and build on the strengths that accompany a dyslexic profile rather than dwell on difficulties and challenges.

As a key researcher and commentator of many years standing, Stanovich has written extensively on dyslexia, on inclusivity and the impact of the labelling of differences. His approach appears to be principally two-fold. Firstly to fuel the debate about whether dyslexia per se exists, a viewpoint that has emerged from the research and scientific difficulties that he claims arise from attempts to differentiate dyslexia from other poor literacy skills; and secondly that given that dyslexia in some definition or another is a quantifiable characteristic, argues strongly that as long as the learning disability agenda remains attached to aptitude-achievement discrepancy measurement and fails to be a bit more self-critical about its own claims, (Stanovich, 1999), its home in the field of research will advance only slowly. Indeed a short time later he described the learning disabilities field as 'not ... on a scientific footing and continu[ing] to operate on the borders of pseudoscience' (Stanovich, 2005, p103). His position therefore fiercely advocates a more inclusive definition of learning disabilities as being one which effectively discards the term entirely because it is 'redundant and semantically confusing' (op cit, p350) a persistent argument that others echo. Lauchlan & Boyle (2007) broadly question the use of labels in special education, concluding that aside from being necessary in order to gain access for support and funding related to disability legislation, the negative effects on the individual can be considerable and may include stigmatization, bullying, reduced opportunities in life and perhaps more significantly, lowered expectations about what a 'labelled' individual can achieve (ibid, p41) as also reported above. Norwich (1999, 2008, 2010) has written extensively about the connotations of labelling, persistently arguing for a cleaner understanding of differences in educational contexts because labels are all too frequently stigmatizing and themselves disabling, referring to the 'dilemma of difference' in relation to arguments 'for' and 'against' curriculum commonality/differentiation for best meeting the educational needs of differently-abled learners. Armstrong & Humphrey (2008) suggest a 'resistance-accommodation' model to explain psychological reactions to a 'formal' identification of dyslexia, the 'resistance' side of which is typically characterized by a disinclination to absorb the idea of dyslexia into the self-concept, possibly resulting from perhaps more often, negatively vicarious experiences of the stigmatization attached to 'difference', whereas the 'accommodation' side is suggested to take a broadly positive view by making a greater effort to focus and build on the strengths that accompany a dyslexic profile rather than dwell on difficulties and challenges.

McPhail & Freeman (2005) have an interesting perspective on tackling the challenges of transforming learning environments and pedagogical practices into genuinely more inclusive ones by exploring the 'colonizing discourses' that disenfranchise learners with disabilities or differences through a process of being 'othered'. Their conclusions broadly urge educationalists to have the courage to confront educational ideas and practices that limit the rights of many student groups (ibid, p284). Pollak (2005) reports that one of the prejudicious aspects of describing the capabilities of individuals under assessment is the common use of norm-referenced comparisons. This idea is inherently derived from the long-established process of aligning measurements of learning competencies to dubious evaluations of 'intelligence', standardized as these might be (for example Wechsler Intelligence Scale assessments to identify just one), but which fail to accommodate competencies and strengths which fall outside the conventional framework of 'normal' learning capabilities - that is, in accordance with literacy-dominant education systems. Norwich (2013) also talks more about 'capabilities' in the context of 'special educational needs', a term he agrees, is less than ideal. The 'capability approach' has its roots in the field of welfare economics, particularly in relation to the assessment of personal well-being and advantage (Sen, 1999) where the thesis is about individuals' capabilities to function. Norwich (op cit) puts the capability approach into an educational context by highlighting focus on diversity as a framework for human development viewed through the lens of social justice which is an interesting parallel to Cooper's thesis on diversity taken from a neurological perspective as discussed above. This all has considerable relevance to disability in general but particularly to disability in education where the emphasis on everyone becoming more functionally able (Hughes, 2010) is clearly aligned with the notion of inclusivity and the equal accommodation of difference because the focus is inherently positive as opposed to dwelling on deficits. and connects well with the principles of universal design for learning outlined above.

McPhail & Freeman (2005) have an interesting perspective on tackling the challenges of transforming learning environments and pedagogical practices into genuinely more inclusive ones by exploring the 'colonizing discourses' that disenfranchise learners with disabilities or differences through a process of being 'othered'. Their conclusions broadly urge educationalists to have the courage to confront educational ideas and practices that limit the rights of many student groups (ibid, p284). Pollak (2005) reports that one of the prejudicious aspects of describing the capabilities of individuals under assessment is the common use of norm-referenced comparisons. This idea is inherently derived from the long-established process of aligning measurements of learning competencies to dubious evaluations of 'intelligence', standardized as these might be (for example Wechsler Intelligence Scale assessments to identify just one), but which fail to accommodate competencies and strengths which fall outside the conventional framework of 'normal' learning capabilities - that is, in accordance with literacy-dominant education systems. Norwich (2013) also talks more about 'capabilities' in the context of 'special educational needs', a term he agrees, is less than ideal. The 'capability approach' has its roots in the field of welfare economics, particularly in relation to the assessment of personal well-being and advantage (Sen, 1999) where the thesis is about individuals' capabilities to function. Norwich (op cit) puts the capability approach into an educational context by highlighting focus on diversity as a framework for human development viewed through the lens of social justice which is an interesting parallel to Cooper's thesis on diversity taken from a neurological perspective as discussed above. This all has considerable relevance to disability in general but particularly to disability in education where the emphasis on everyone becoming more functionally able (Hughes, 2010) is clearly aligned with the notion of inclusivity and the equal accommodation of difference because the focus is inherently positive as opposed to dwelling on deficits. and connects well with the principles of universal design for learning outlined above.

![]()

Impact of the process of identification

Having said all this, exploring the immediate emotional and affective impact that the process of evidencing and documenting a learner's study difficulties has on the individual under scrutiny is a pertinent and emerging research field. (Armstrong & Humphrey, 2008). Perhaps as an indication of an increasing awareness of the value of finding out more about how an individual with dyslexia feels about their dyslexia, there have been relatively recent research studies that relate life/learning histories of individuals with dyslexia (eg: Dale & Taylor, 2001, Burden & Burdett, 2007, Evans, 2013, Cameron & Billington, 2015, Cameron, 2016). One intriguing study attempts to tease out meaning and understanding from these through the medium of social media (Thomson et al, 2015) where anonymous 'postings' to an online discussion board hosted by a dyslexia support group resulted in three, distinct categories of learning identities being established: learning-disabled, differently-enabled, and societally-disabled. The researchers observed from these postings that while some contributors took on a mantle of 'difference' rather than 'disability', expressing positiveness about their dyslexia-related strengths, most appeared to be indicating more negative feelings about their dyslexia, with some suggesting that their 'disability identity' had been imposed on them (ibid, p1339) not the least arising through societal norms for literacy.

The pilot study that underpins this current research project (Dykes, 2008) also explored feelings about dyslexia which was designed as a secondary aspect of its data collection process but it emerged that individuals responding to the enquiry were keen to express their feelings about their dyslexia and how they felt that it impacted on their studies. In the light of the findings of this earlier research, perhaps it should have been unsurprising to note in this current project, the significant number of questionnaire replies that presented quite heartfelt narratives about the respondents' dyslexia. Some 94% of the 98 QNR replies returned by students with dyslexia included data at this level. The complete portfolio of narratives can be accessed on the project webpages here and it is intended to explore this rich pool of qualitative data as the constraints of the project permit although it is anticipated that it likely that further, post-project research will be required in due course to fully understand it.

It may be through a collective study (in the future) of others' research in this area that conclusions can be drawn relating to the immediate impact on individuals when they learn of their dyslexia. However in the absence of any such meta-analysis being unearthed so far, even a cursory inspection of many of the learning histories presented in studies that have been explored to date generally reveals a variety of broadly negative and highly self-conscious feelings when individuals learn of their dyslexia. Although such reports strongly outweigh those from other learners who claimed a sense of relief that the 'problem' has been 'diagnosed' or that an explanation has been attributed to remediate their feelings of stupidity as experienced throughout earlier schooling, it is acknowledged that there is some evidence of positive experiences associated with learning about ones dyslexia, as reported earlier. This current project aims to be a contributor to this discourse as one facet of the questionnaire used to collect data sought to find out more about how dyslexic students learned about their dyslexia. A development feature of the project will co-relate the disclosures provided to respondents' narratives about how they feel about their dyslexia where this information has also been provided. As yet, a methodology for exploring this has still to be developed and this process may also be more likely to be part of the future research that it is hoped will stem from this current project.

However, and as already explored variously above, it seems clear that in the last two decades at least, many educators and researchers in the broad domain of revisiting the scope and presentation of tertiary-level learning and thinking are promoting a more enlightened view. It is one that rails against the deficit-discrepancy model of learning difference. It seeks to displaces entrenched ideology rooted in medical and disability discourses with one which advocates a paradigm shift in the responsibility of the custodians of knowledge and enquiry in our places of scholarship to one which more inclusively embraces learning and study diversity. There is a growing advocacy that takes a social-constructionist view to change the system rather than change the people (eg: Pollak, 2009), much in line with the Universal Design for Learning agenda briefly discussed above. Bolt-on 'adjustments', well-meaning as they may be, will be discarded because they remain focused on the 'disabling' features of the individual and add to the already burdensome experiences of being part of a new learning community - a factor which of course, affects everyone coming to university.

To explore this point a little further, an example that comes to mind is technology 'solutions' that are designed to embed alternative practices and processes for accessing and manipulating information into not only so-called 'disabled' learners' but into everyone's study strategies. These are to be welcomed and great encouragement must be given to institutions to experiment with and hopefully adopt new, diverse practices of curriculum delivery although the rapid uptake of this seems unlikely in the current climate of financial desperation and austerity being experienced by many of our universities at this time. Having said this, encouraging or perhaps even requiring students to engage with technology in order to more easily facilitate inclusivity in study environments can raise other additional learning issues such as the investment in time necessary to master the technology (Dykes, 2008). These technologies may also remain too non-individualized nor easy-to-match to the learning strengths and weaknesses of many increasingly stressed students (Seale, 2008). So for differently-abled learners, these 'enabling' solutions may still require the adoption of additional, compensatory study practices, and may often be accompanied by an expectation to have to work and study harder than others in their peer-group in an academy which requires continuous demonstration of a high standard of literacy as a marker of intellectual capability (Cameron & Billington, 2015) and which moves to exclude and stigmatize those who cannot produce the expected academic outcome in the 'right' way (Collinson & Penketh, 2013). Eventually we may see this regime displaced by processes that will provide a much wider access to learning resources and materials that are available in a variety of formats and delivery mediums, the study of which can be assessed and examined through an equally diverse range of processes and procedures that carry equal merit. No apology is made for persistently returning to this point.

To explore this point a little further, an example that comes to mind is technology 'solutions' that are designed to embed alternative practices and processes for accessing and manipulating information into not only so-called 'disabled' learners' but into everyone's study strategies. These are to be welcomed and great encouragement must be given to institutions to experiment with and hopefully adopt new, diverse practices of curriculum delivery although the rapid uptake of this seems unlikely in the current climate of financial desperation and austerity being experienced by many of our universities at this time. Having said this, encouraging or perhaps even requiring students to engage with technology in order to more easily facilitate inclusivity in study environments can raise other additional learning issues such as the investment in time necessary to master the technology (Dykes, 2008). These technologies may also remain too non-individualized nor easy-to-match to the learning strengths and weaknesses of many increasingly stressed students (Seale, 2008). So for differently-abled learners, these 'enabling' solutions may still require the adoption of additional, compensatory study practices, and may often be accompanied by an expectation to have to work and study harder than others in their peer-group in an academy which requires continuous demonstration of a high standard of literacy as a marker of intellectual capability (Cameron & Billington, 2015) and which moves to exclude and stigmatize those who cannot produce the expected academic outcome in the 'right' way (Collinson & Penketh, 2013). Eventually we may see this regime displaced by processes that will provide a much wider access to learning resources and materials that are available in a variety of formats and delivery mediums, the study of which can be assessed and examined through an equally diverse range of processes and procedures that carry equal merit. No apology is made for persistently returning to this point.

To identify or not to identify? - that is the question

So a dilemma arises about whether or not to (somehow) identify learning differences. On the one hand, there is a clear and strong argument that favours changing the system of education and learning so that difference is irrelevant, whilst on the other, the pragmatists argue that taking such an approach is idealistic and unachievable and that efforts should be focused on finding better and more adaptable ways to 'fix' the learner.

So a dilemma arises about whether or not to (somehow) identify learning differences. On the one hand, there is a clear and strong argument that favours changing the system of education and learning so that difference is irrelevant, whilst on the other, the pragmatists argue that taking such an approach is idealistic and unachievable and that efforts should be focused on finding better and more adaptable ways to 'fix' the learner.

In the short term at least the pragmatists' approach is the more likely one to be adopted but in doing so, constructing an identification process for learning differences that attributes positiveness onto the learning identity of the individual rather than burdens them with negative perceptions of the reality of difference would seem to be a preference. This is important for many reasons, not the least of which is that an assessment/identification/diagnosis that focuses on deficit or makes the 'subject' feel inadequate or incompetent is likely to be problematic however skilfully it may be disguised as a more neutral process. Not the least this may be due to the lasting, negative perception that an identification of dyslexia often brings, commonly resulting in higher levels of anxiety, depressive symptoms, feelings of inadequacy and other negative-emotion experiences which are widely reported (eg: Carroll & Iles, 2006, Ackerman et al, 2007, Snowling et al, 2007). This is especially important to consider in the design of self-report questionnaire processes where replies are likely to be more reliable if the respondents feel that the responses they provide are not necessarily portraying them poorly, particularly so in the self-reporting of sensitive information that may be adversely affected by social influences and which can impact on response honesty (Rasinski et al, 2004).

Devising a process for gauging the level of dyslexia that an individual may present is only of any value in an educational context. Indeed, it is hard to speak of this without referring to severity of dyslexia which is to be avoided - in the context of this paper at least - because it instantly contextualizes dyslexia into the deficit/discrepancy model. However and as already mentioned, in the current climate labelling a learner with a measurable learning challenge does open access to learning support intended to compensate for the challenge. At university level, this access is based on the professional judgment of a Needs Assessor and on an identification of mild, moderate or severe dyslexia, with the extent of learning support that is awarded being balanced against these differentiated categories of disability, even though the differentiation boundaries appear arbitrary and highly subjective. This support in the first instance is financial and economic, notably through the award of the Disabled Students' Allowance (DSA) which provides a substantial level of funding for the purchase of technology, other learning-related equipment and personally-tailored study support tutorials. This is usually in addition to wider 'reasonable adjustments' provided as various learning concessions by the institution, such as increased time to complete exams. To date, and with the exception of a study by Draffan et al (2007) into student experiences with DSA-awarded assistive technology to which one conclusion indicated the significant numbers of recipients electing not to receive training in the use of the technology that they had been supplied with, no other research enquiries have been found so far that explore the extent to which assistive technology provided through the DSA, for example, is effective in properly ameliorating the challenges that face the dyslexic student learning in current university environments, nor indeed to gauge the extent to which this expensive provision is even utilized at all by recipients. Research into the uptake of differentiated study support for students with dyslexia also identified a substantial time lag between a formal needs assessment and the arrival of any technology equipment for many students (Dykes, 2008) which is likely to be a contributing factor to the low uptake of this type of learning support because students simply become tired of waiting for the promised equipment and instead just get on with tacking their studies as best they can. So it comes as no surprise that the award of DSA funding for students with dyslexia is under review at this time as perhaps this is an indication of how financial custodians have also observed the apparent ambivalency towards technology assistance from students in receipt of the funding, which ironically may be more due to systemic failures than to a perceived vacillation amongst students - more of this below.

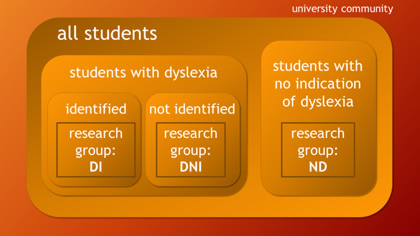

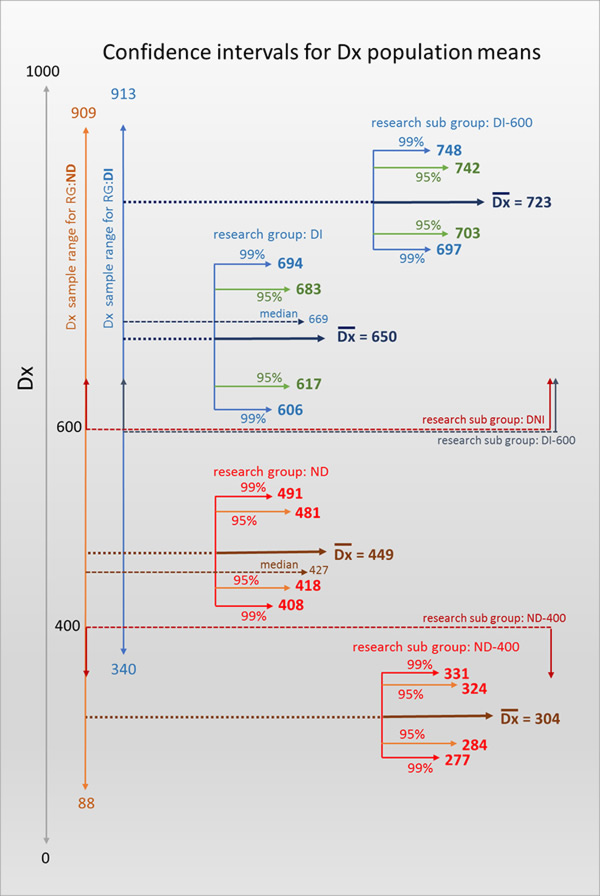

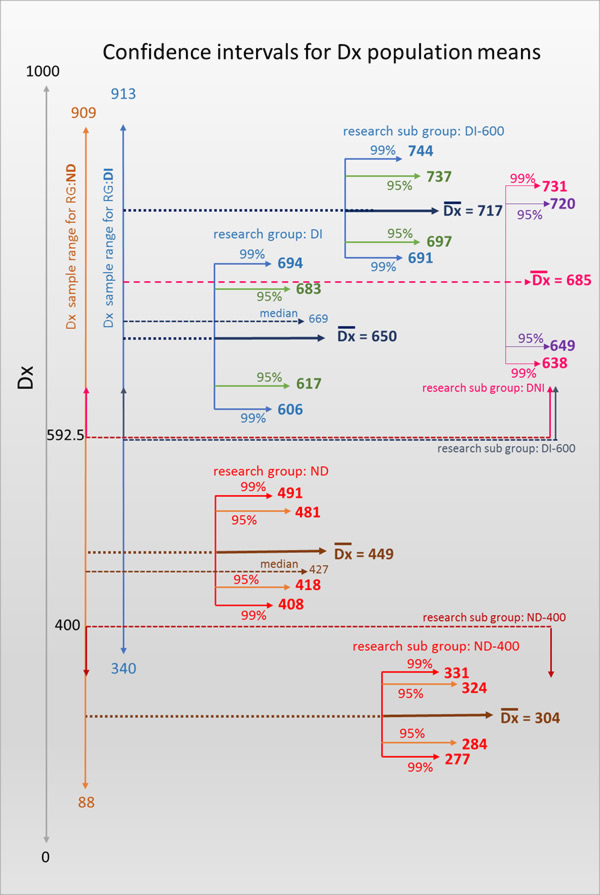

However, to return to the point, one of the main aspects of this research project is a reliance on finding students at university with an unidentified dyslexia-like profile as a core process for establishing measurable differences in academic agency between identified and unidentified 'dyslexia', with this being assessed through the Academic Behavioural Confidence metric developed by Sander & Sanders (2006). So to achieve this, incorporating some kind of evaluator that might be robust enough to find these students is key to the research methodology. A discussion about how this has been achieved is presented in the next section.

MEASURING DYSLEXIA - "HOW DYSLEXIC AM I?"

MEASURING DYSLEXIA - "HOW DYSLEXIC AM I?"

It might be thought that 'measuring dyslexia' is a natural consequence of 'identifying dyslexia' but the commonly used dyslexia screening tools offer, at best, an output that requires interpretation and in UK universities, this is usually the task of a Disability Needs Assessor. Given an indication of dyslexia that results from a screening, what usually follows is a recommendation for a 'full assessment' which, in the UK at least, has to be conducted by an educational psychologist. However even such a comprehensive and daunting 'examination' does not produce much of a useful measurement to describe the extent of the dyslexic difference identified, other than a generally summative descriptor of 'mild', 'moderate' or 'severe', some assessment tools do provide scores obtained on some of the tests that are commonly administered. Nevertheless, these are generally are of use only to specialist practitioners and not usually presented in a format that is very accessible to the individual under scrutiny.

One student encountered in this researcher's role as a dyslexia support specialist at university recounted that on receiving the result of his assessment which indicated that he had a dyslexic learning difference, he asked the assessor: 'well, how dyslexic am I then?' He learned that his dyslexia was 'mild to moderate' which left him none the wiser, he said. One of his (dyslexic) peers later recounted that his view was that he did not think dyslexia was real because he believed that 'everyone if given the chance to prove it, could be a bit dyslexic' (respondent #9, Dykes, 2008, p95). His modest conclusion to account for his learning challenges was that his problem was that he was just not as intelligent as others, or thought that perhaps his lack of confidence from an early age decreased his mental capacity.

On the one hand, certainly for school-aged learners, identifying dyslexia is rooted in establishing capabilities that place them outside the 'norm' in assessments of competencies in phonological decoding and automaticity in word recognition for example, and in other significantly reading-based evaluations. This has been mentioned briefly earlier. Some identifiers include an element of assessment of working memory such as the digit span test, which has relevance to dyslexia because working memory abilities have clear relationships with comprehension. If a reader gets to the end of a long or complex sentence but fails to remember the words at the beginning long enough to connect with the words at the end then clearly this compromises understanding. All of these identifiers also carry quantifiable measures of assessment although they are discretely determined and not coalesced into an overall score or value. Besides, there is widespread agreement amongst psychologists, assessors and researchers that identifiers used for catching the dyslexic learner at school do not scale up very effectively for use with adults (eg: Singleton et al, 2009). This may be especially true for the academically able learners that one might expect to encounter at university who can, either actively or not, mask their difficulties (Casale, 2015) or even feign them if they perceive advantage to be gained (Harrison et al, 2008) as also reported above. However, recent studies continue to reinforce the idea that dyslexia is a set of quantifiable cognitive characteristics (Cameron, 2016) but which extend beyond the common idea that dyslexia is mostly about poor reading, certainly once our learner progresses into the university environment.

So the last two decades or so have seen the development of a number of assessments and screening tests that aim to identify – but not specifically to measure - dyslexia in adults and particularly in higher education contexts as a response to the increasing number of students with dyslexia attending university. Aside from this being a route towards focused study skills support interventions, when a screening for dyslexia indicates that a full assessment from an educational psychologist is prudent, this becomes an essential component for any claim to the Disabled Students' Allowance (DSA) although ironically the assessment has to be financed by the student and is not recoverable as part of any subsequent award. It is of note, however, that with a recent refocusing of the target group of disabled students who are able to benefit from the DSA (Willetts, 2014) access to this element of support is likely to be withdrawn for the majority of students with dyslexia at university in the foreseeable future although for this current academic year (2016/17) it is still available. This may be an indication that dyslexia is no longer 'officially' considered as a disability, which is at least consistent with the standpoint of this research project, although it is more likely that the changes are as a direct result of reduced government funding to support students with additional needs at university rather than any greater understanding of dyslexia based on informed, research-based recommendations.

So the last two decades or so have seen the development of a number of assessments and screening tests that aim to identify – but not specifically to measure - dyslexia in adults and particularly in higher education contexts as a response to the increasing number of students with dyslexia attending university. Aside from this being a route towards focused study skills support interventions, when a screening for dyslexia indicates that a full assessment from an educational psychologist is prudent, this becomes an essential component for any claim to the Disabled Students' Allowance (DSA) although ironically the assessment has to be financed by the student and is not recoverable as part of any subsequent award. It is of note, however, that with a recent refocusing of the target group of disabled students who are able to benefit from the DSA (Willetts, 2014) access to this element of support is likely to be withdrawn for the majority of students with dyslexia at university in the foreseeable future although for this current academic year (2016/17) it is still available. This may be an indication that dyslexia is no longer 'officially' considered as a disability, which is at least consistent with the standpoint of this research project, although it is more likely that the changes are as a direct result of reduced government funding to support students with additional needs at university rather than any greater understanding of dyslexia based on informed, research-based recommendations.

An early example of a screening assessment for adults is the DAST (Dyslexia Adult Screening Test) developed by Nicholson & Fawcett (1997). This is a modified version of an earlier screening tool used with school-aged learners but which followed similar assessment principles, that is, being mostly based on literacy criteria although the DAST does include non-literacy based tests, namely a posture stability test – which seems curiously unrelated although it is claimed that its inclusion is substantiated by pilot-study research - a backward digit span test and a non-verbal reasoning test. Literature review appears to indicate that some researchers identify limitations of the DAST to accurately identify students with specific learning disabilities, for example Harrison & Nichols (2005) felt that their appraisal of the DAST indicated inadequate validation and standardization. Computerized screening tools have been available for some time, such as the LADS (Lucid Adult Dyslexia Screening, (Lucid Innovations, 2015)) which claims to generate a graphical report that collects results into a binary categorization of dyslexia as the individual being 'at risk' or 'not at risk'. Aside from being such a coarse discriminator, 'at risk' again appears to be viewing dyslexia through the lens of negative and disabling attributes. The screening test comprises 5 sub-tests which measure nonverbal reasoning, verbal reasoning, word recognition, word construction and working memory (through the backward digit span test) and indicates that just the final three of these sub-tests are dyslexia-sensitive. The reasoning tests are included based on claims that to do so improves screening accuracy and that results provide additional information 'that would be helpful in interpreting results' (ibid, p13), that is, provides a measure of the individual's 'intelligence' - which, in the light of Stanovich's standpoint on intelligence and dyslexia mentioned earlier, is of dubious worth.

Warmington et al (2013) responded to the perception that dyslexic students present additional learning needs in university settings, implying that as a result of the increased participation in higher education in the UK more generally there is likely to be at least a corresponding increasing in the proportion of students who present disabilities or learning differences. Incidentally,, Warmington et al quotes HESA figures for 2006 as 3.2% of students entering higher education with dyslexia. A very recent enquiry directly to HESA elicited data for 2013/14 which indicated students with a learning disability accounting for 4.8% of the student population overall (Greep, 2015), and also representing some 48% of students disclosing a disability, which certainly will make students with dyslexia the biggest single group of students categorized with disabilities at university, such that they are currently labelled. It is of note that the HESA data is likely to be an under-reporting of students with a learning disability - that is, specific learning difficulty (dyslexia) because where this occurs together with other impairments or medical/disabling conditions this is reported as a separate category with no way of identifying the multiple impairments. At any rate, both of these data are consistent with the conclusions that the number of students with dyslexia entering university is on the rise. Given earlier mention above about dyslexia being first-time identified in a significant number of students post-entry it is reasonable to suppose that the actual proportion of dyslexic students at university is substantial. Indeed, this research is relying on finding 'hidden' dyslexics in the university community in order to address the research questions and hypothesis.

Warmington et al (2013) responded to the perception that dyslexic students present additional learning needs in university settings, implying that as a result of the increased participation in higher education in the UK more generally there is likely to be at least a corresponding increasing in the proportion of students who present disabilities or learning differences. Incidentally,, Warmington et al quotes HESA figures for 2006 as 3.2% of students entering higher education with dyslexia. A very recent enquiry directly to HESA elicited data for 2013/14 which indicated students with a learning disability accounting for 4.8% of the student population overall (Greep, 2015), and also representing some 48% of students disclosing a disability, which certainly will make students with dyslexia the biggest single group of students categorized with disabilities at university, such that they are currently labelled. It is of note that the HESA data is likely to be an under-reporting of students with a learning disability - that is, specific learning difficulty (dyslexia) because where this occurs together with other impairments or medical/disabling conditions this is reported as a separate category with no way of identifying the multiple impairments. At any rate, both of these data are consistent with the conclusions that the number of students with dyslexia entering university is on the rise. Given earlier mention above about dyslexia being first-time identified in a significant number of students post-entry it is reasonable to suppose that the actual proportion of dyslexic students at university is substantial. Indeed, this research is relying on finding 'hidden' dyslexics in the university community in order to address the research questions and hypothesis.

The York Adult Assessment-Revised (YAA-R) was the focus of the Warmington et al study which reported data from a total of 126 students of which 20 were known to be dyslexic. The YAA-R comprises several tests of reading, writing, spelling, punctuation and phonological skills that is pitched most directly to assess the abilities and competencies of students at university (ibid, p49). The study concluded that the YAA-R has good discriminatory power of 80% sensitivity and 97% specificity but given that the focus of the tests is almost entirely on literacy-based activities, it fails to accommodate assessments of the wide range of other strengths and weaknesses often associated with a dyslexic learning profile that are outside the envelope of reading, writing and comprehension. A similar criticism might be levelled at the DAST as this largley focuses on measuring literacy-based deficits. Indeed, Channock et al (2010) trialed a variation of the YAA-R adjusted in Australia to account for geographical bias in the UK version as part of a search for a more suitable assessment tool for dyslexia than those currently available. Conclusions from the trial with 23 dyslexic students and 50 controls were reported as 'disappointing' due not 'to the YAA-R's ability to differentiate between the two groups, but with it's capacity to identify any individual person as dyslexic' (ibid, p42) as it failed to identify more than two-thirds of previously assessed dyslexic students as dyslexic. Channock further narrates that self-reporting methods proved to be a more accurate identifier - Vinegrad's (1994) Adult Dyslexia Checklist was the instrument used for the comparison. A further criticism levelled at the YAA-R was that it relied on data collected from students in just one HE institution, suggesting that that differences between students in different institutions was an unknown and uncontrollable variable which was not accounted for but which might influence the reliability and robustness of the metric.

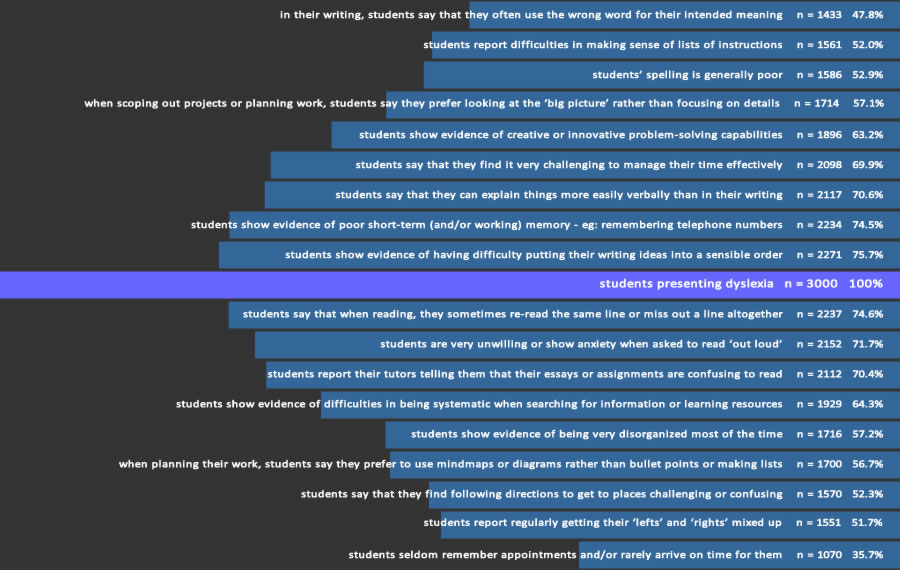

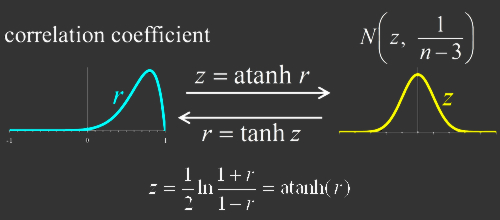

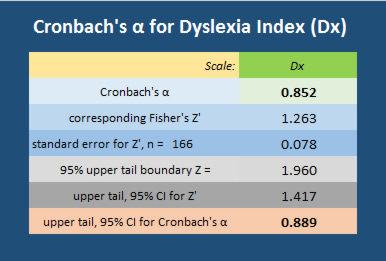

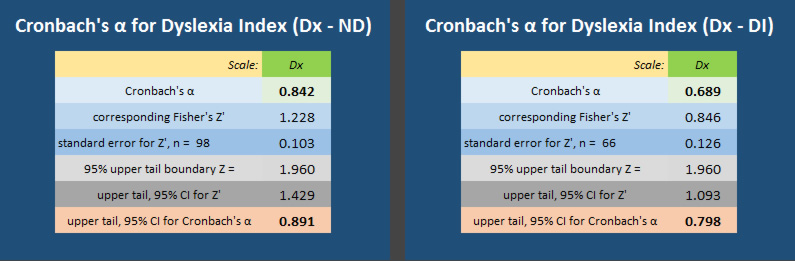

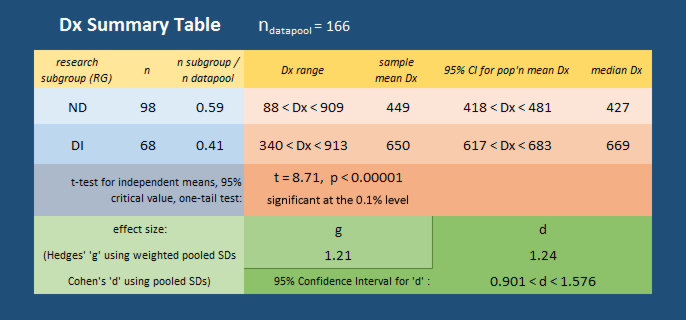

Aside from the use of norm-referenced evaluations for identifying dyslexia as a discrepancy between intellectual functioning and reading ability being controversial, one interesting study highlighted the frequently neglected factors of test reliability and error associated with a single test score, with a conclusion that a poor grasp of test theory and a weak understanding of the implications of error can easily lead to misdiagnosis (Cotton et al, 2005) in both directions – that is, generating both false positives and false negatives.