- When I was learning to read at school, I often felt I was slower than others in my class;

- My spelling is generally good;

- I find it very challenging to manage my time efficiently;

- I can explain things to people much more easily verbally than in my writing;

- I think I'm a highly organized learner;

- In my writing, I frequently use the wrong word for my intended meaning;

- I generally remember appointments and arrive on time;

- When I'm reading, I sometimes read the same line again or miss out a line altogether;

- I have difficulty putting my writing ideas into a sensible order;

- In my writing at school, I often mixed up similar letters like 'b' and 'd' or 'p' and 'q';

- When I'm planning my work I use diagrams or mindmaps rather than lists or bullet points;

- I'm hopeless at remembering things like telephone numbers;

- I find following directions to get to places quite straightforward;

- I prefer looking at the 'big picture' rather than focusing on the details;

- My friends say I often think in unusual or creative ways to solve problems;

- I find it really challenging to make sense of a list of instructions;

- I get my 'lefts' and 'rights' easily mixed up;

- My tutors often tell me that my essays or assignments are confusing to read;

- I get in a muddle when I'm searching for learning resources or information;

- I get really anxious if I'm asked to read 'out loud'.

discourse study-blog | resources | lit review maps | profiles

enquiry dysdefs QNR | dysdims QNR | research QNR

thesis overview | literature | research design | analysis & discussion | closing reflections

Draft (2017-18)

Draft (2017-18)

Analysis and Discussion

This section presents the data analysis of the information acquired through the research questionnaire together with a continuous discussion about the outcomes.

The first part presents an overview of the demographics of the datapool showing the distribution of research participants by gender; study level, ranging from access or foundation year students through to post-doctoral researchers; study status, being either home or overseas students; and finally, dyslexia disclosure and how these participants learned of their dyslexia. Commentary will be included that interprets these data in comparison to national statistics relating to students in Higher Education in the UK and also key points which emerge will be related to others' research and the underlying theory. This narrative process will continue throughout this section with the most pertinent discussion points being extracted and reviewed in the Discussion section of the thesis which follows.

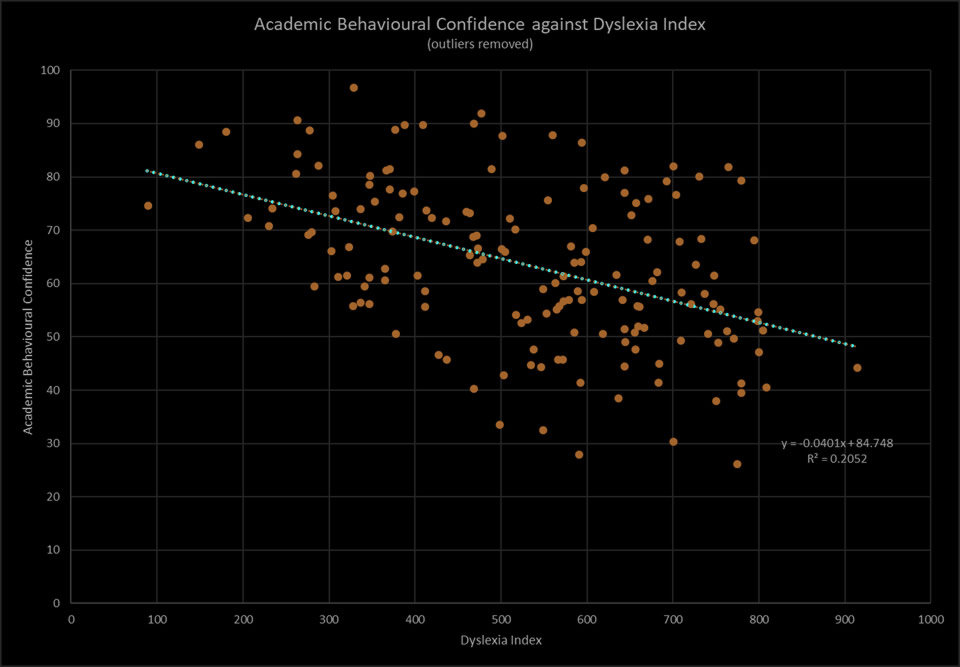

This opening section is followed by a general desription of the statistical tools and processes that have been used to explore the data and the rationales that shaped the analysis. The next sections present in turn, details of the mechanisms that were employed to extract meaning from the data collected through the Dyslexia Index (Dx) Profiler section of the questionnaire and through the Academic Behavioural Confidence Scale. Following this, a detailed section presents the findings that emerged from analysis of the inter-relationships between Dyslexia Index and Academic Behavioural Confidence overall, but also how these metrics were more deeply explored through Principal Component Analysis and hence what this revealed when looking at a factors of Dyslexia and of Academic Behavioural Confidence presented as a matrix of inter-relationships.

Lastly, a short section will briefly discuss the data retrieved from the other metrics in the research questionnaire - that of the 6, psychometric subscales, explaining why this is not included in the data analysis at this time and how this data might be explored as part of a future research project. [possibly delete this short para?]

The Analysis and Discussion section concludes with a summary of the most important findings with interpretations about what they are revealing in terms of the relationships between dyslexia and academic confidence in university students and why this is important to understand. [377/ #]

- ABSTRACT

- ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- PROJECT OVERVIEW

- RESEARCH QUESTIONS

- STANCE

- RESEARCH IMPORTANCE

-

THEORETICAL PERSPECTIVES

THEORETICAL PERSPECTIVES

-

DYSLEXIA

DYSLEXIA

- A complex phenomenon or a psuedo-science?

- Dyslexia: the definition issues

- Dyslexia as a multifactoral difference

- Disability, deficity, difficulty, difference or none of these?

- Labels, categories, dilemmas of difference, inclusivity

- Impact of the process of identification

- To Identify or Not To Identify? - that is the question

- Measuring dyslexia - "how dyslexic am I?"

-

ACADEMIC CONFIDENCE - theoretical foundations of the construct

ACADEMIC CONFIDENCE - theoretical foundations of the construct

-

ACADEMIC SELF-EFFICACY - the parent construct for academic confidence

ACADEMIC SELF-EFFICACY - the parent construct for academic confidence

- The construct of academic self-efficacy

- The relationships between academic self-efficacy and academic achievement

- Confidence as a learning attribute

- The location of academic confidence within the construct of academic self-efficacy

- Academic Behavoural Confidence

- Use of the ABC scale in this research project

-

-

RESEARCH DESIGN

RESEARCH DESIGN

-

RESULTS, ANALYSIS and DISCUSSION

RESULTS, ANALYSIS and DISCUSSION

- LIMITATIONS

- CONCLUSIONS

- DIRECTIONS FOR FUTURE RESEARCH

- REFERENCES

-

APPENDICES

APPENDICES

Analysis and Discussion

Analysis and Discussion Section Contents:

- OVERVIEW

- TERMINOLOGY

- Research Questions

- ANALYSIS OUTCOME SUMMARY

- DATA ANALYSIS REPORT

- DEMOGRAPHICS

- HOW DYSLEXIC STUDENTS LEARNED OF THEIR DYSLEXIA

- The impact of receiving a diagnosis of dyslexia on Academic Behavioural Confidence

- DYSLEXIA INDEX

(Dx)

- Preliminary data anlsysis outcomes - descriptive statistics

- Setting boundary values for Dx

- PRINCIPAL COMPONENT ANALYSIS(PCA)

- Applying PCA to the datapool

- Factorial Analysis of Dyslexia Index (Dx)

- The primary PCA on Dyslexia Index

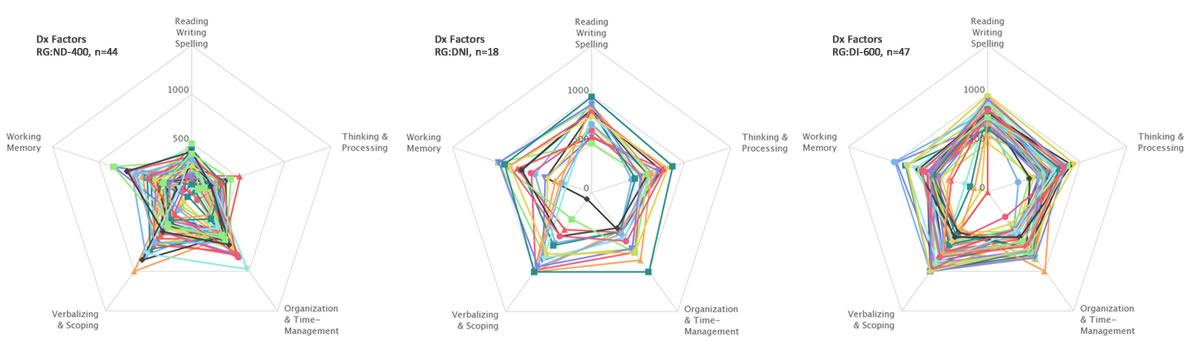

- Dyslexia Index Factors by Research Subgroup

- Comparing differences in Dyslexia Index dimensions between research subgroups

- Factorial Analysis of Academic Behavioural Confidence (ABC)

- Dx Factor x ABC Factor MATRIX

- Effect size between Academic Behavioural Confidence

- Key outcomes

- Applying multiple regression analysis

- Analysis summary and discussion

Overview

Data was acquired from the deployment of an electronic questionnaire across the student community at Middlesex University both through an invitation-to-participate to all university students published on the university's 'home' internal webpage and also through a targeted invitation-to-participate to the specific cohort of students registered with the university's Disability and Dyslexia Service.

On completion of the questionnaire, submitting it generated an e-mail containing the complete dataset which was sent to the researcher's university e-mail account. In total, 183 replies were received of which only 17 were discarded either because the questionnaire was less than 50% completed, or spoiled in some other way. Hence this provided a participant datapool of 166 complete datasets.

As reported in an earlier section, the questionnaire was very carefully designed to be an appealing, interactive, self-report webpage which incorporated innovative features that were intended to ensure that participant interest and hence engagement would be maintained throughout. The structure was divided into 5 sections which were accessed and viewable in turn, a design feature intended to reduce possible effects of questionnaire fatigue which might otherwise have occured should partipants have had sight of the complete questionnaire and hence perceive it to be lengthy and complex. This design approach, together with careful attention being paid to colours, contrasts and fonts, was adopted to try to ensure that the questionnaire was as accessible and dyslexia-friendly as possible, whilst at the same time retain a visual appeal and an innovative design so as to be interesting and attractive to all research participants.

The opening section collected demographic data relating to gender, known learning challenges, student resident category and study status. Participants recorded their answers using selections from drop-down menu lists or selecting from check-box items. An important part of this first part of the research questionnaire focused on participants who acknowledged their dyslexia by requesting these students to indicate how they learned of their circumstance. To do this, participants used a two drop-down menu lists of options to complete a simple sentence which then indicated how they learned about their dyslexia. It was assumed that this disclosure would have been through one of the formalized methods of dyslexia assessment either conducted with adult students at university or prior to commencing their courses.

The section which followed presented the Academic Behavioural Confidence Scale (Sander & Sanders, 2003, 2006, 2009) in its complete, 24-scale-item format with stem items unabridged nor modified in any way. Participants registered 'how confident they were that they will be able to ...' using an innovative sliding scale ranging from 0% to 100% (confident), hence replacing the conventional, 5-anchor-point Likert scale item recording process adopted in every other deployment of the Academic Behavioural Confidence Scale in research studies and projects to date. The rationale for this design approach has been discussed in the previous, Research Design, section.

On completion of the ABC Scale, participants were requested to work through the next section of 36 stem-item statements which were measuring the 6 psychometric scales of Learning Related Emotions, Anxiety regulation and Motivation, Academic self-efficacy, Self-esteem, Learned Helplessness, and Academic Procrastination. Each scale comprised 6 stem-item statements and participants also recorded their answers using continuous-scale sliders with end points of 0% and 100% agreement respectively. The detailed reporting of results recorded in this section and the subsequent analysis has been excluded from this thesis firstly because it became clear as a result of an early inspection and outline analysis of the complete datapool that sufficient data had been acquired through the ABC Scale and the Dyslexia Index Profiler to address the research hypotheses, and secondly that to include sufficient background literature review and later data analysis would have generated a finished thesis in excess of submission limitations. Hence data collected in this section has been saved for later use in a subsequent research project.

The final section of the questionnaire to collect quantitative data presented the 20-point Dyslexia Index Profiler and the now-familiar continuous-scale sliders were presented to partipants for recording their % agreement with each of the stem-item statements.

Lastly, participants were invited to qualify or enhance the data they had provided by writing in an unlimited free-text area anything else about their learning challenges or strengths, or any other aspects about how they approached their studies at university. Entering data into this section was optional.

[717/ # ]

Terminology

The meanings of labels, terms, acronyms and designations used in the reporting and discussion of the data, results and analysis is presented in the table below where it is particularly important to note the designations assigned to research groups and subgroups. Within the complete datapool there are two, distinct research groups: students who acknowledged their dyslexia by indicating this on the questionnaire that they submitted; and students who alternatively indicated that they did not have any specific learning challenges that they knew about. Within each of these groups participants were sifted into subsets determined by the Dyslexia Index (Dx) value generated by their responses to that section of the questionnaire. The boundary value was set at Dx = 592.5. The rationale and justification for setting the boundary value at this point has been explained in the previous, Research Design section of this thesis (here). Students who had declared their dyslexia and whose Dyslexia Index value was above the boundary value, that is, Dx > 592.5, formed the CONTROL subgroup (i.e. subset) and students who had indicated no awareness of any specific learning challenges and whose Dyslexia Index was Dx > 592.5 formed the TEST subgroup. A further subgroup of students was established as a distinct subset of the group of participants who indicated no specific learning challenges where these participants presented a Dyslexia Index Dx < 400, that is, students indicating a very low level of dyslexia-ness. This subgroup is referred to as the BASE subgroup.

The meanings of labels, terms, acronyms and designations used in the reporting and discussion of the data, results and analysis is presented in the table below where it is particularly important to note the designations assigned to research groups and subgroups. Within the complete datapool there are two, distinct research groups: students who acknowledged their dyslexia by indicating this on the questionnaire that they submitted; and students who alternatively indicated that they did not have any specific learning challenges that they knew about. Within each of these groups participants were sifted into subsets determined by the Dyslexia Index (Dx) value generated by their responses to that section of the questionnaire. The boundary value was set at Dx = 592.5. The rationale and justification for setting the boundary value at this point has been explained in the previous, Research Design section of this thesis (here). Students who had declared their dyslexia and whose Dyslexia Index value was above the boundary value, that is, Dx > 592.5, formed the CONTROL subgroup (i.e. subset) and students who had indicated no awareness of any specific learning challenges and whose Dyslexia Index was Dx > 592.5 formed the TEST subgroup. A further subgroup of students was established as a distinct subset of the group of participants who indicated no specific learning challenges where these participants presented a Dyslexia Index Dx < 400, that is, students indicating a very low level of dyslexia-ness. This subgroup is referred to as the BASE subgroup.

| TERM | abbreviation | MEANING |

| datapool | the complete set of data acquired from all the participant questionnaires included in the project; n = 166 | |

| dataset | the complete set of data provided by one participant | |

| research group | RG | a subgroup of the complete dataset |

| research group ND | RG:ND | the subset of the dataset containing participants who returned a disclosure of no specific learning challenges known; n = 98 |

| research group DI | RG:DI | the subset of the dataset containing participants who indicated that they were dyslexic; n = 68 |

| Dyslexia Index | Dx | the value returned by the Dyslexia Index Profiler section of the main questionnaire. Dyslexia Index falls within the range 0 to 1000 with a higher score indicating a higher level of dyslexia-ness. |

| research subgroup DNI | RG:DNI | the subset of research group ND containing participants who returned a Dyslexia Index of Dx > 592.5 - this is the group of participants who returned no disclosure of dyslexia but whose Dyslexia Index suggests a high level of dyslexia-ness - hence these are the participants of greatest interest in this project -this is the TEST GROUP |

| research subgroup DI-600 | RG:DI-600 | the subset of research group DI containing dyslexic participants who returned a Dyslexia Index of Dx > 592.5 - this is the CONTROL GROUP |

| research subgroup ND-400 | RG:ND-400 | the subset of research group ND containing participants who returned a Dyslexia Index of Dx < 400. This is the BASE GROUP |

| boundary value | this refers to the Dyslexia Index value which set the upper or lower Dx limit for determining a research subgroup. A report on how these values were established is provided in the previous section, Research Design. | |

| Academic Behavioural Confidence | ABC | the value returned by the Academic Behavioural Confidence Scale section of the main questionnaire, falling within the range 0 to 100 |

| ABC24 | referring to the complete, original Academic Behavioural Confidence Scale of 24 scale items | |

| ABC24-# | referring to one of the five factors of the Academic Behavioural Confidence 24-item Scale, determined in this study through factor analysis; # = 1,2,3,4,5 | |

| ABC17 | referring to the reduced, 17-scale item ABC Scale | |

| Principal Component Analysis | PCA | the method of dimension reduction analysis used to establish the five factors of ABC and the five factors of Dyslexia Index in this project |

Research questions and null hypotheses:

Recall the research questions that this project is addressing:

Recall the research questions that this project is addressing:

- Do university students who know about their dyslexia present a significantly lower academic confidence than their non-dyslexic peers?

- Ho(1) = There is no difference between dyslexic and non-dyslexic students' levels of academic confidence;

- AH (1) = Non-dyslexic students present a higher level of academic confidence than their dyslexic peers.

If so, can particular factors in their dyslexia be identified as those most likely to account for the differences in academic confidence and are these factors absent or less-significantly impacting in non-dyslexic students?

- Do university students with no formally identified dyslexia but who show evidence of a dyslexia-like learning and study profile (i.e. quasi-dyslexic) present a significantly higher academic confidence than their dyslexia-identified peers?

- Ho(2) = There is no difference between dyslexic and apparently dyslexic students' levels of academic confidence;

- AH (2) = Quasi-dyslexic students present a higher level of academic confidence than their dyslexic peers.

If so, are the factors identified above in the profiles of dyslexic students absent or less-significantly impacting in students with dyslexia-like profiles?

Analysis outcome summary:

Thus the analysis of the data is in two stages: firstly it will be established that the Dyslexia Index Profiler is a sufficiently robust discriminator of dyslexia-ness to enable it to sift student research participants into the respective research groups and subgroups set out in the research design; and secondly the levels of Academic Behavioural Confidence between the groups and subgroups will be compared.

Hence the hypotheses of this research project can be properly addressed, which is to initially establish that dyslexic students at university present a lower level of academic confidence, as indicated using the standardized, Academic Behavioural Confidence Scale, than their non-dyslexic peers. To enable this, data from participants in the CONTROL group, RG:DI-600, will be compared with data from participants in the BASE group, RG:ND-400.

Secondly it will be established that students with previously unidentified, dyslexia-like study profiles, as indicated through use of the Dyslexia Index Profiler to evaluate their level of dyslexia-ness (Dx), present a higher level of academic confidence, as indicated using the ABC Scale, than their dyslexia-identified peers; data from participants in the TEST subgroup, RG:DNI will be compared with data in the CONTROL subgroup, RG:DI-600.

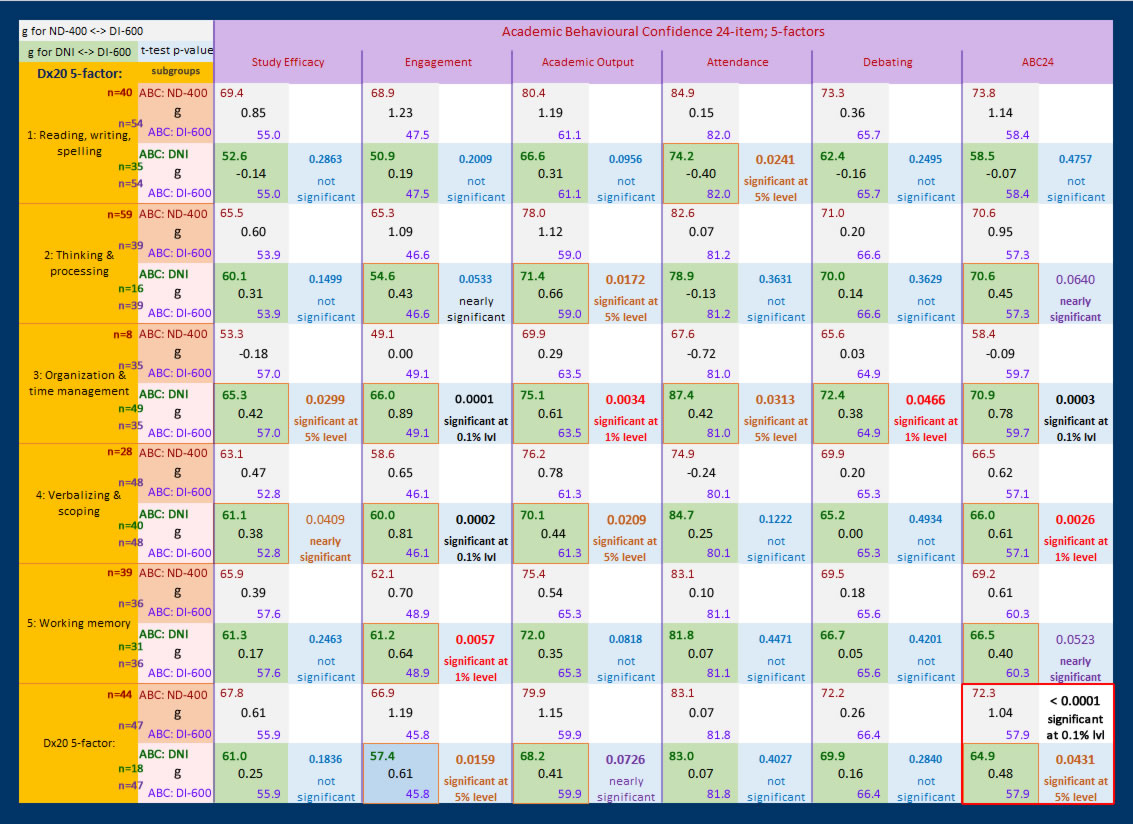

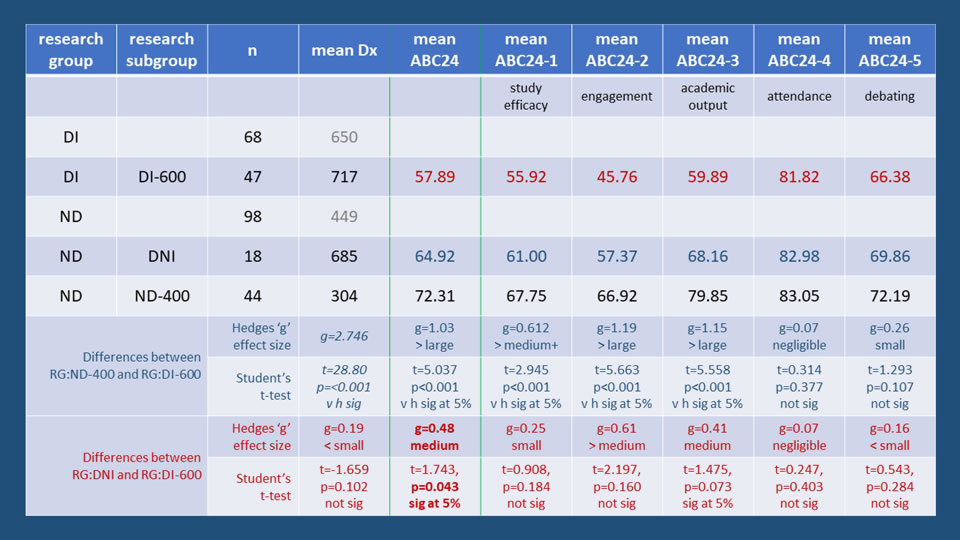

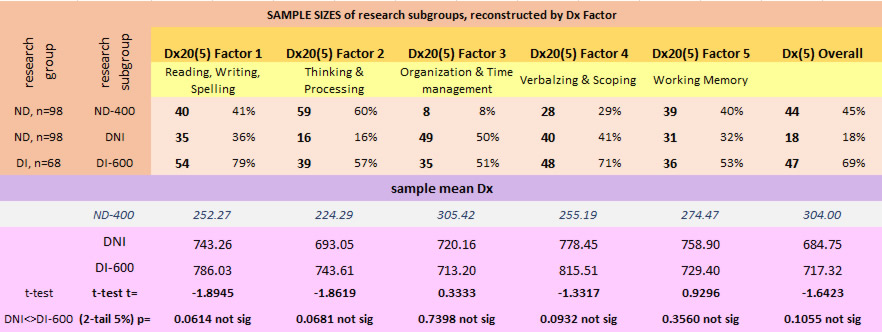

The summary table below presents a results overview for the data analysis conducted. It shows the mean Dx value for the two, principal research groups, DI, ND, and for the research subgroups, DNI, DI-600 and ND-400, representing respectively the TEST group, the CONTROL group and the BASE group, together with the corresponding mean values of Academic Behavioural Confidence both overall, using Sander & Sanders' original, 24-item Scale, together with the mean values of ABC on a factor-by-factor basis where these 5 factors have been established through a factorial analysis of the data collected from the complete datapool, the process for which is described in detail below.

Effect size measures will be the main points of statistical evidence used to argue against the Null Hypotheses presented above, with these data analysis outcomes comprehensively supported by the more conventional measure of statistical difference between independent sample means, Student's t-test. Hence the key findings in the summary table below are the effect size differences between means and the corresponding outcomes from the t-test analyses of the differences between the mean values. A one-tail test was conducted because in every case the alternative hypothesis was that i) the mean values for RG:ND-400 are higher than the mean values for RG:DI-600 and ii) the mean values for RG:DNI are higher than the mean values for RG:DI-600. Homegeneity of variances was established using Levene's Test and according to the output, the appropriate p-value was taken. Hedges 'g' effect size is used because the sample sizes are significantly different in all comparison cases which requires the weighted, pooled standard deviations to be used.

Key Outcomes

1. In comparison with their non-dyslexic peers (RG:ND), students with a declared dyslexic learning difference (RG:DI) present a significantly lower level of Academic Behavioural Confidence, with a large effect size difference (g=1.03) between the mean values of ABC24. There is sufficient evidence to reject the Null Hypothesis (1) and accept the Alternative Hypothesis (1).

2. Apparently non-dyslexic students (RG:DNI) but who show a level of dyslexia-ness that is comparable to their declared, dyslexic peers present a significantly higher level of Academic Behavioural Confidence in comparison to a control group of declared, dyslexic peers (RG:DI-600), with a medium effect size (g=0.48) difference between the mean values of ABC24. There is sufficient evidence to reject the Null Hypothesis (2) and accept the Alternative Hypothesis (2).

Data and Analysis Report

1. Demographics

Datapool demographics overview

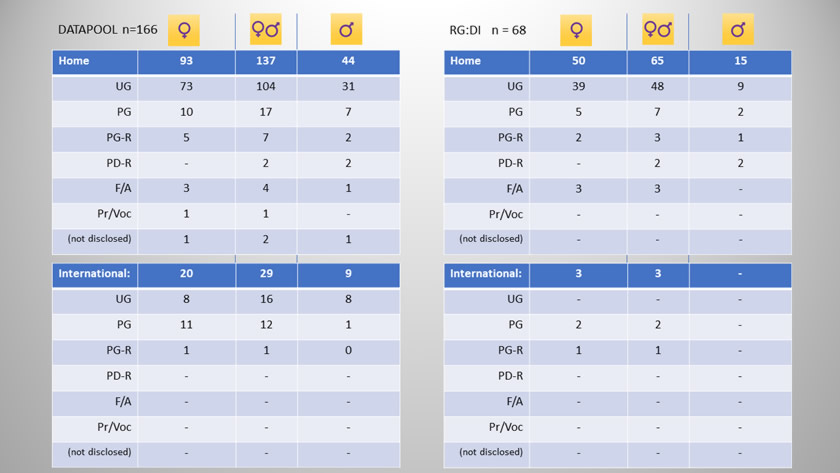

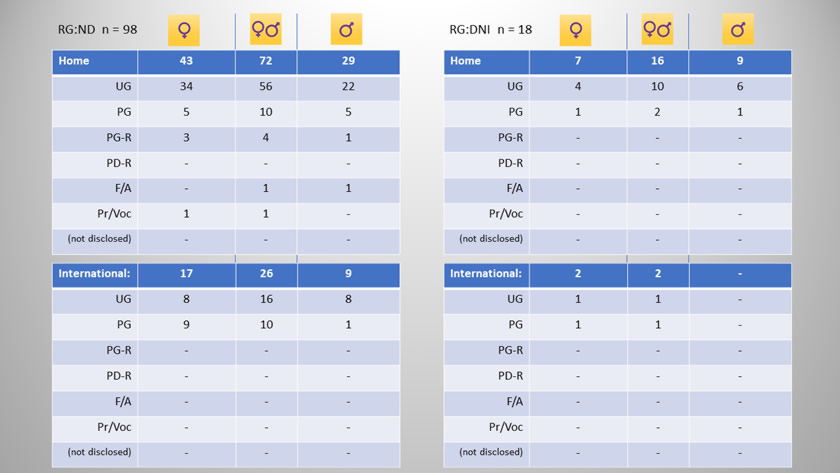

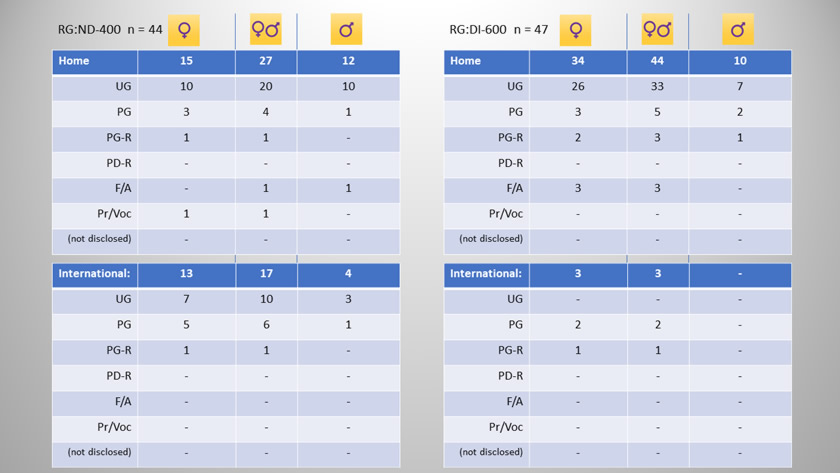

At the end of the questionnaire deployment period a total of n=183 questionnaire replies had been received. Of these, n=17 were discarded because they were more than 50% incomplete. The demographic distribution of participants according to Research Subgroup; gender; student residency: home or international; and student study status: undergraduate (UG), post-graduate (PG), post-graduate research (PG-R), post-doctoral research (PD-R), attending a Foundation or Access Course (F/A), attending a Professional or Vocational Course (Pr/Voc), is shown in tabular and chart form below. A commentary follows which examines each demographic in the context of this study and where appropriate, in relation to wider, national data on student demographics nationally.

Datapool and Research Subgroup: DI

Research Subgroups: ND, and DNI (Test Group = subset of RG:ND)

Research Subgroups: ND-400 (= subset of RG:ND), and DI-600 (Control Group = subset of RG:DI)

1.1 Demographics of Research Groups and Subgroups

The charts show the relative sizes of research groups and subgroups as defined by the Dyslexia Index (Dx) boundary values, Dx=400 and Dx=592.5.

The top chart presents the proportion of students of the complete datapool (n=166), who disclosed their dyslexia on the research questionnaire (RG:DI, n=68) against those who indicated no specific learning challenges (RG:ND, n=98). A sample size of n=30 is widely considered to be the minimum for any reasonable statistical analysis to be conducted (Cohen & Manion, 1980) although it is accepted that there is no definitive ruling on sample size because the minimum value needs to be considered in the light of the proposed analysis (Robson, 1993). So by taking these advisories into account it is considered that a complete datapool sample size of n=166 with the two principal research groups dividing the datapool in the ratio 41%:59% (RG:DI, n=68 : RG:ND, n=98) the number of students who returned replies to the research questionnaire is sufficient for a meaningful statistical analysis to be conducted.

The second chart indicates the relative subgroup proportions of research group ND, that is, students who reported no specific learning challenges. It can be seen that in accordance with the Dx boundary values set for the project, 18% of students in research group ND presented levels of dyslexia-ness that were above the critical value of Dx > 592.5 and hence were more in line with students who had disclosed their dyslexia. This is presented in the third chart which indicates more than two-thirds of the respondents who disclosed their dyslexia also demonstrated a level of dyslexia-ness above the critical Dx boundary value set at Dx=592.5. As reported in an earlier section (here) the most recent data acquired from HESA* (Greep, 2017) indicated that students in UK HE institutions who disclosed a learning disability accounted for 4.8% of the student population overall, this being a proportional rise of 50% from the figure quoted by Warmington (2013) for 2006. This is at least one further statistic which supports the observation of many studies that the prevalence of dyslexic students in UK universities is rising for a variety of reason not least through recent initiatives for widening participation in higher education amongst traditionally under-represented groups, particularly those with dyslexia who may have been previously disenfranchised from more formal education (Collinson & Penketh, 2010). Greep pointed out that this figure (4.8%) was an indicator of the incidence of all 'defined' learning disabilities and in addition to dyslexia, included others such as dyspraxia, ADHD and Asperger's Syndrome for example. Greep added that there is currently no mechanism in place in the current data collection process at HESA for discriminating students with dyslexia as a subgroup of those indicating learning disabilities and hence it is reasonable to suppose that the proportion of declared dyslexic students in the UK university population in 2013/14 is likely to be less than the 4.8% quoted, although Greep did indicate HESA's view that dyslexia is likely to be the most represented subgroup. It seems likely that this supposition is based on the generally accepted statistical evidence about the incidence of these learning disabilities more widely. For example, Casale (2015) quoted (unreferenced) HESA data which indicated that 5.5% of university students are disabled where presumably this figure included all disabilities of which students with learning disabilities is a subset, further claiming that dyslexia accounted for 40% of these students - that is, 2.2% of the student population as a whole. Casale drew a comparison with data provided by the British Dyslexia Association (2006) claiming that dyslexia is evident in approximately 10% of the general population of the UK. However estimates of the prevalence of the traditionally considered dyslexia as a reading difficulty in children vary considerably with studies suggesting rates ranging from 5% to 17.5% (Shaywitz & Shaywitz, 2005)

Hence in the first instance it might be concluded that determining true levels of incidence of dyslexia either at university, in compulsory education, or especially in the general population is a challenging statistic to establish. This is certainly consistent with many of the arguments presented in earlier sections of this thesis discussing issues about how dyslexia is defined and hence relating to challenges in measuring it. As a result, it seems reasonable to conclude that it is likely that the true proportion of dyslexic students at university is inevitably higher than the supposedly established data indicates. Secondly, the data collected in this project which, on the basis of the definitions of the metrics used, indicates that a substantial proportion of apparently non-dyslexic students may indeed present dyslexic learning differences - the 18% indicated in the second chart - which adds to the weight of wider research and anecdotal evidence that dyslexia amongst university students is widely under-reported (Richardson & Wydell, 2003, Stampoltzis & Polychronopoulou, 2008) and/or continues to be unidentified on entry (Singleton et al, 1999).

It is also interesting note that of the research group of declared dyslexic students in this project (n=68), 21 presented a level of dyslexia-ness below the critical boundary value of Dx = 592.5. By the criteria established for this project at least, this indicates that these students might have been mis-identified as dyslexic despite their declaration of being so, which was presumably based on a earlier, conventional process of assessment.

*Higher Education Statistics Agency

[868/ # ]

1.2 Gender

For the complete datapool, female research participants outnumbered males by a factor of approximately 2 to 1. That is, there were twice as many females as males in the datapool. (113:53 = 67%:33%, n=166).

Dyslexic student participants who were recruited from the targeted e-mail invitation sent out on the University's Dyslexia and Disability Service's e-mail distribution list and who subsequently were designated as research group DI were in the F:M ratio 53:15 (= 78%:22%, n=68) showing that female participants outnumbered males by a factor of more than 3 to 1, whereas student participants recruited through the open invitation to all students as published on the University's student intranet 'home' webpage, and who subsequently formed research group ND (n=98), were distributed by gender in the F:M ratio 60:38 (= 61%:39%) which although shows that female students still responded more positively to the invitation to participate than males when compared with the gender-analysed response rate, the female bias is lower.

In comparison to the gender distribution of students in the UK more generally, HESA* figures for the academic year 2016/17 for students enrolled on courses at HE institutions showed that although female students outnumbered males, the ratio is much closer to an even balance (F:M 57%:43%). For the UK generally, the ratio of females to males in the population as a whole in 2016 was F:M 51%:49% (Office for National Statistics). It is beyond the scope of this study to explore the reasons behind gender imbalances amongst higher education students however it is interesting to note the apparently significant differences in research participation invitation response rates between the two recruitment processes, although the main reason for this may simply be that students registered with the University's Dyslexia and Disability Service may be heavily biased towards females. This at least would be consistent the argument that at university, male students are less likely than females to engage with learning development or support services either as a result of a known, hidden or unknown disability or learning difference or indeed for any other reason (Fhloinn et al, 2016. Kessels & Steinmayr, 2013, Kessels et al, 2014, Ryan et al. 2009) which is also consistent with some gender differences reported in levels of engagement with education and learning for a variety of reasons but especially in the self-regulated learning contexts which is dominant in higher education settings (Virtanen & Nevgi, 2010). This gender disparity has also been extensively observed and reported anecdotally within my own professional experience and domain of functioning in university learning development services, however it is beyond the scope of this project to engage in a deeper analysis of the reasons behind these differences.

[442/ # ]

1.3 Student residency status

In this project, participants were asked to identify whether they were a 'home' student or an 'international/overseas' student - that is, without separating non-UK EU students from all overseas students. The charts (right) present the distribution of research participants by domicile and for comparison, national data from HESA* for 2016/17 is shown. Although this demonstrates a similar distribution it must be added that the HESA figures are for student enrolment for that academic year rather than a measure of the domicile distribution of all students studying at UK institutions at that time. However, it is reasonable to accept that the ratio of 'home' students to non-UK students would not be significantly different were an aggregated figure used, were it available.

Hence the domicile distribution of the datapool in this study can be considered as representative of the wider student community studying at university in the UK.

However, when domicile distribution is considered at a micro- as opposed to macro-level it is interesting to note (from the data tables above) that only 3 out of the 68 participants in Research Group: DI identified themselves as non-UK students, a figure of just 4.4% which might be an indication of the very low incidence of non-UK dyslexic students studying at UK universities. It is beyond the scope of this thesis to conduct a detailed exploration to account for this, but it is likely that one reason for this apparently low figure may instead be an indication of the lack of available access to the university's Dyslexia and Disability Service for non-UK students with dyslexia. Hence very few non-UK students would have been on the Service's e-mail distribution list to receive the invitation to participate in this research project. The reason for this may be that as non-UK students are not eligible for formal dyslexia identification through the provision of the Disabled Students' Allowance in the UK and as such either may not be eligible to access the learning development and support provided by the Service to dyslexic students or may not even be aware that such a service exists. However it might also be the case that access to dyslexia idenfitication processes in their home countries for these non-UK students is less prevalent than in the UK for a variety of reasons, a fact that might be supported in this research project by comparing the ratio of non-UK to home students for both identified dyslexic students (RG:DI) and apparently-unidentified dyslexic students (RG:DNI). For dyslexic students in research group DI this ratio is the 3 in 68 (4.4%) as mentioned above. Students sifted into research subgroup DNI as a result of their Dyslexia Index values of Dx > 592.5, the ratio is 3 in 18 (16.7%) which, at face value alone, suggests that there exists a significant proportion of un-identified, apparently dyslexic, non-UK students in this datapool at least. However as this subgroup is small (n=18) it would be inappropriate to draw significant conclusions from this disparity 4.4%/16.7%, as it may be accounted for through margins of error. It would be necessary to establish a much larger subgroup of apparently non-dyslexic students who were presenting high levels of dyslexia-ness and hence examine the distribution ratio of 'home' to non-UK students to enable a more robust conclusion to be drawn.

[547 / # ]

1.4 Student study status

It was considered useful to obtain data relating to the level of study programmes of students participating in the research not least to determine whether the research datapool constituted a reasonable cross-sectional match to the wider student community. If so, then it follows that conclusions derived from the research outcomes might reasonably be considered as representative of students attending UK universities more generally.

The charts present the proportions of student participants in the datapool according to level of their study programmes and comparisons with nationally collected data for 2016/17*. To enable a like-for-like comparison as far as is possible, those participants in this project who indicated study for professional or vocational qualifications were grouped with post-graduates, with post-grad- and post-doc researchers being combined. It is of note too that the national data labelled here as those studying at Foundation/Access level also includes those studying at pre-level 4 (1st year undergraduate).

From these it can be seen that in comparison to national data, undergraduate respondents in this study are over-represented although when undergraduates and foundation/access level students are combined, the proportions are closer (76% : 66%).

*HESA 2016/17 available at: https://www.hesa.ac.uk/data-and-analysis/students/whos-in-he, accessed on: 16 April 2018)

[201 / # ]

2. How dyslexic students learned of their dyslexia

The impact of receiving a diagnosis of dyslexia on Academic Behavioural Confidence

One aspect of the enquiry aimed to find out more about how dyslexia becomes known to students who have declared it on their QNR response. This is pertinent as the research hypotheses imply that it may be the label of dyslexia which is one of the factors that contribute to reduced Academic Behavioural Confidence in students with dyslexia in comparison to their peers but especially how that label is attributed. Further that this may impact on academic achievement due to reduced academic self-efficacy possibly associated with the effects of stigma on the social identity of dyslexic students at university (Jodrell, 2010). One of the undercurrents to the project is the recognition of the stigma that is reportedly associated with the label of dyslexia (Morris & Turnbull, 2007, Lisle & Wade, 2013). The sub-hypothesis being tested is that students whose dyslexia was diagnosed to them as a disability have significantly lower levels of academic confidence in comparison to students whose dyslexia was made known to them in ways that referred to neither 'diagnosis' nor to 'disability'. If evidence emerges to support this hypothesis, then the contention being suggested is that their lower acadeimc confidence is an indication of the negative internalization of dyslexia into their self-identity due to a perception that the outcome of their 'disability diagnosis' will be that they will be valued less by their peers or society more generally as a result of it, a characteristic typically associated with stigmatization (Goffman, 1963 in Ainlay et al, 2013).

To explore this, QNR respondents who were acknowledging their dyslexia were also invited to complete a sentence in the opening section of the QNR to report how they learned about their dyslexia. It was assumed that such students had previously participated in a formal dyslexia screening and/or assessment, typically conducted through the conventional process adopted by UK universities, or that their dyslexia assessment had been conducted previously during their earlier years in education. The sentence required selections to be made from two drop-down menu lists so that on completion it would indicate how the respondent was informed about their dyslexia as an outcome of a screening or a full assessment.

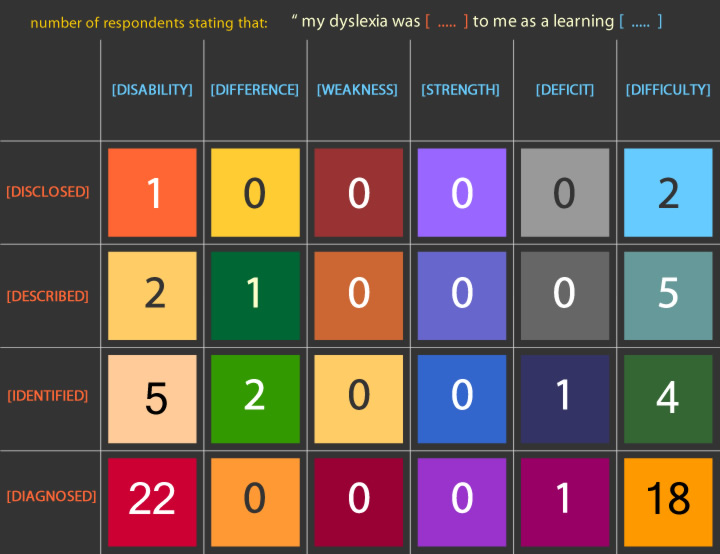

The summary grid below sets out this data from the 68 responses who had acknowledged their dyslexia which constituted research group DI. The grid total is actually 64, as 4 respondents in research group DI did not select options. The grid presents the number of respondents who selected particular combinations of options. For example, in the first row of the grid it can be seen that 2 respondents completed the sentence as: 'My dyslexia was DISCLOSED to me as a learning DIFFICULTY'. What is especially relevant to this part of data analysis is that the majority of dyslexic students reported that their dyslexia was ‘diagnosed’ with diagnosed as a disability recorded slightly more often in comparison with disagnosed as a difficulty. This it seemed reasonable to explore the Academic Behavioural Confidence of students whose dyslexia had been diagnosed as a difficulty or a disability, with the expectation for this to be at a reduced level when compared to their otherwise-identified peers.

It seems reasonable to argue that when informing an individual about their newly discovered dyslexia, using the most neutral and unbiased phraseology is likely to be the least discomfiting to them and so identifying dyslexia as a difference seems to be the most appropriate turn of phrase to use. Hence it would be expected that this would reduce the likelihood of dyslexia being internalized into the student's self-identity as a medical condition, tacitly implied by ‘diagnosing’ it, especially given the largely negative construction of disability in society more generally (eg: Connor & Lynne, 2006, Phelan, 2010).

To date, no other studies have been found which specifically explore the impact of how dyslexia is communicated to the student concerned following a screening or assessment at university although some studies do examine the psychosocial experiences of receiving an identification of dyslexia. For example Nalavany et al (2011) claimed to have conducted the first study to explore how confirmed and self-identified dyslexia impacted on adult perspectives of their experiences associated with their dyslexia. This research was concerned less with how the adults in the research group (n=75) experienced the impact of their dyslexia on their learning and more so with how it affected their day-to-day lives and the study did not report on the ways in which individuals had learned of their dyselxia. However many of the participants recollected school and learning experiences that were 'hurtful, embarrassing, and scary', and that their teachers misunderstood their learning challenges (ibid, p74) which at least documents how the lasting effects of experiencing 'being different' in younger years can persist into adulthood.

Another important and relevant study by Armstrong & Humphrey (2008) has already been referred to in the literature review section of this thesis but its main findings are particularly pertinent to this section despite their research datapool being adolescents at school or college rather than adults studying at university. Their study was also concerned with the psychosocial components of living with the label of dyslexia (ibid, p96) and although the outcome of their project led to the proposal of a fresh model for understanding how individuals assimilate their dyslexia into their self-identity (the Resistance-Accommodation Model as briefly discussed earlier), their model clearly has merit for gaining a clearer understanding about the 'dyslexic self', despite the study persistently referring to how individuals accommodated their diagnosis of dyslexia. The use of this phraseology did not appear to have been considered as a factor that might influence an individual's internalization of new knowledge about their dyslexia following its identification through a conventional assessment process, even though the authors did acknowledge that 'the amount of resistance or accommodation displayed by individuals clearly stems at least in part from their perception of dyslexia' (ibid, p99). My argument here is that this perception of dyslexia might also, in part, be influenced by the ways in which an identification of it is communicated and that has been the purpose of this part of the research questionnaire. Through just this cursory analysis and reflection on the meaning of the data produced, this is probably indicating the need for a deeper, follow-up study to be conducted at a later time.

Thus it seems likely that as long as dyslexia remains perceived even as a 'difference' and hence dyslexic people internalize themselves as 'different', there will remain a stigma attached to the label. Having argued this, it is interesting to note however that at least one research study concluded that an important process in understanding stigma associated with the labelling of difference is that the role of labelling needs deconstructing (Riddick,2000). One suggestion that emerged from that study was that the ownership of the labelling process by individuals concerned needs to have a focus on self-definition, personal understanding and elements of control (ibid, p665), which tacitly implies that part of the identification process (although Riddick uses 'diagnosis' rather than identification) should include an element of positive counselling as part of the 'telling' procedures to the individual concerned so that the process of incorporating this new self-knowledge into the self-identity might be less psychologically unsettling. This is the view taken by Ho (2004) whose strongly argued essay on the dilemma about labelling learning disability (dyslexia) supports the view that attributing a dyslexic identity to a learner can be as unnecessary as it can be counter-productive when the uniqueness of individuals' learning is taken as the context, further arguing that curricula and delivery need to be designed flexibly to accommodate this - a view that strongly resonates with the stance of this current research project. Mention of Riddick's and Ho's studies have been included as part of the discussion in an earlier section of this thesis (here) where I have briefly discussed the 'dilemma of difference' originally suggested by Minow and more lately researched by Norwich amongst others.

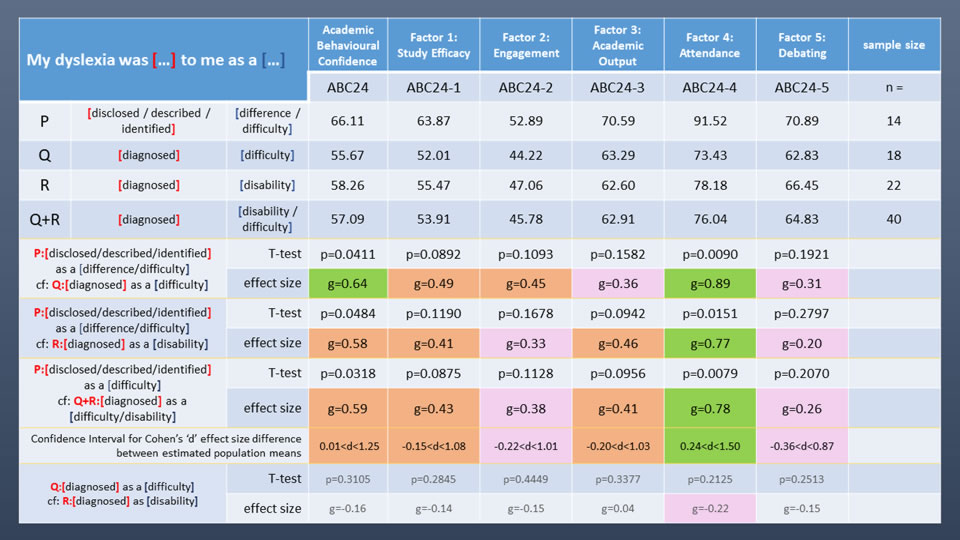

So how does the data collected in this study from the 68 research participants who declared their dyslexia in the research questionnaire fit in with these reflections? Responses from students who disclosed, described or identified their dyslexia as a difference or a difficulty were sifted into a single subgroup leaving those whose dyslexia was diagnosed as as a disability or a difficulty being sifted into a comparator subgroup. (4 participants who declared their dyslexia did not complete the declaration sentence and hence for the purposes of this analysis the complete group comprises 64 participants). The table below sets out the summary of a statistical analysis to compare the mean values of Academic Behavioural Confidence overall and of Academic Behavioural Confidence factors as determined from a principal component analysis of the complete datapool, a description of which is presented later in this section (here). Student's t-test was used to determine whether these data presented a significant difference between means using a one-tail test, because we are testing the hypothesis that students whose dyslexia was disclosed/described/identified as a difference/difficulty present a significantly higher level of academic behavioural confidence than students whose dyslexia was diagnosed as a disability/difficulty; equal variances were assumed and tested using Levene's test with the normality of the data being established through the Shapiro-Wilk test. Arguably more interesting and more informative than t-test outcomes are effect sizes between means, where it has been observed through the review of the more recent, relevant literature for this project that this is being increasingly widely used as an outcome measure amongst researchers in psychology, educational psychology and the social sciences more generally. Here, as with data analysed and reported below, Hedges 'g' is the effect size measure chosen and the rationale for using this over the more conventional Cohen's 'd' has been outlined in the previous section where the research methodology for the study was reported. For this analysis, an effect size of g < 0.20 is considered small to negligible, a value of 0.20 ≤ g < 0.45, small to medium, 0.45 ≤ g ≤ 0.6, medium, and g > 0.6 medium to large. Defining boundary values for effect size measures remains a matter for some debate, perhaps because this is a relatively new statistical measure that has only in recent years attracted interest not least because it establishes a measure of an absolute difference between data sample means. This has been discussed more fully above (here). For the summary table of results below and in order to make the reporting of the outcomes more comprehensible and less repetitive, letter designations P,Q,R, have been added to aid clarity so for example, table row Q presents the subgroup of students whose dyslexia was diagnosed to them as a difficulty, and so forth. The table sets out the mean values for Academic Behavioural Confidence overall and for each of the five ABC factors for each respective combination of the sentence 'my dyslexia was [...] to me as a learning [...]' completed by the participants, together with t-test 'p-values' and effect sizes for the differences between these means.

From the table, interesting and significant observations can be made:

- In the summary row for the comparison of means between students whose dyslexia was disclosed/described/identified to them as a learning difference/difficulty (P) and those whose dyslexia was diagnosed to them as a difficulty (Q) the analysis shows that there is a significant difference at the 5% level (p=0.0411) between the means values of overall Academic Behavioural Confidence, with an effect size of g = 0.64 which is medium to large; when the same first subgroup (P) is compared with students whose dyslexia was diagnosed to them as a disability (R) there is also a significant difference between the overall ABC means at the 5% level (p=0.0484) and a slighly lower effect size of g = 0.58. It is somewhat surprising that the effect size was greater when dyslexia was diagnosed as a difficulty rather than as a disability, however given the small sample sizes it is likely that this is within margins of error and the p-values and effect sizes are broadly the same. Nevertheless, to explore this a little further, t-test and effect size calculations were conducted between subgroups Q and R (at the bottom of the table) and as expected, small or negligible effect sizes were obtained together with no significant differences between the overall ABC means nor ABC-factor means being established from the t-test.

- Hence the most significant (sic) results in relation to the discussion above are the comparision of means and effect sizes between the subgroups of students whose dyslexia was disclosed, described or identified to them as a learning difference or difficulty, and students whose dyslexia was diagnosed as a difference or disability (P, and Q+R). For this comparison of means for academic behavioural confidence overall, a significant result at the 5% level is indicated (p=0.0318) with a medium effect size of 0.59. So for the data collected in this study and within the limitations on drawing conclusions due to the small sample sizes, it would appear that students whose dyslexia is diagnosed to them appear to present a significantly lower academic behavioural confidence when compared with students whose dyslexia was identified, described or disclosed to them. This is an important result as it may be suggesting that the phraseology used to communicate new knowledge of a learning difference that may be attributed to dyslexia to a student at university has a measurable impact on the confidence that they subsequently bring to their studies. It must be restated that these sample sizes are small and so any conclusions derived from the analysis of data within them is tentative but it might be an indication of the difference in perception of dyslexia when communicated as a diagnosis rather than more neutrally and might merit a deeper investigation in a subsequent study. For students in this study at least, this does provide some evidence that those whose dyslexia has been diagnosed to them as a difficulty or a disability may have experienced a reduced impact on their academic confidence had their dyslexia been disclosed, described or identified to them as a learning difference. It is unfortunate that so few students in this study learned of their dyslexia as a difference, as it having a greater sample size would have enabled a further, useful layer of analysis to have been added which may have been able to determine whether there is a measurable distinction in academic confidence between those with dyslexia identified as a difficulty and those with dyslexia identified as a difference, which could have added further weight to the argument that paying careful attention to the ways in which a new identification of a dyslexia may be assimilated into an individual's learning identity can have significant, impacting consequences in relation to their confidence in their study approaches at university.

- ABC factors have been determined using factorial analysis (principal component analysis (PCA)) on the data collected for this study and the rationale for conducting PCA on my datapool rather than rely on the factorial analysis conducted by the originators of the ABC Scale (Sander & Sanders, 2006) have been discussed in the Research Design section of this thesis earlier (here), with a more detailed report on the how the outcomes of the statistical analysis derived the factors used in this study being presented below.

The table above presents a breakdown of the outcomes of the t-test and effect size analysis of differences in mean values for each of the five factors that emerged, designated: study efficacy, engagement, academic output, attendance, and debating.

- Note that for all ABC factors, the mean Academic Behavioural Confidence values for students whose dyslexia was disclosed, described or identified to them as a learning difference or difficulty (P) appears substantially higher than for students whose dyslexia was diagnosed (Q,R, and Q+R). Taken at face value, this appears to be suggesting that when dyslexia is diagnosed, this may be one of the impacting factors that contributes towards a reduced level in all factors of academic behavioural confidence as well as in the overall level of academic behavioural confidence in dyslexic students compared with those who have learned of their dyslexia in more neutrally-loaded ways. The Dyslexia Index (Dx) metric has also been analysed using PCA to determine whether there are combinations of factor-by-factor interrelationships between factors of Dyslexia Index and the factors of Academic Behavioural Confidence. The results of the analysis do identify interesting results and a detailed report and discussion is provided below (here).

- In the table row that presents the analysis outcomes for students whose dyslexia was disclosed, described or identified to them as a learning difference or difficulty (P) and students whose dyslexia was diagnosed to them as a difficulty or a disability (Q+R), only for the factor: attendance did the t-test identify a difference between ABC factor means as significant, in fact, a p-value of p=0.0079 being less than the critical p-value of p=0.01 indicates this to be a highly significant difference in means. The effect size of g=0.78 is high and by looking at the mean ABC values for this factor of ABC24-4 = 91.52 (for the subgroup with the summary table designation 'P') and ABC24-4 = 76.04 (Q+R) we can observe that the actual difference is indeed substantial. This outcome suggests that students whose dyslexia is diagnosed may be less diligent in attending their classes, lectures, seminars and other university teaching scenarios than students whose dyslexia had been identified, disclosed or described to them. It is reasonable to hypothesize that this may be due to these students perceiving and internalizing their dyslexia as a clinical condition alluded to through use of the term diagnosis rather than as an identifiable learning difference. It is possible that this induces feelings of discomfort in the company of their student peers should their dyslexia become apparent because these diagnosed dyslexics may have internalized their dyslexia as a perception that there is something wrong with them that they would prefer not to be revealed to their classmates, either explicitly or more likely as inadvertently disclosed by their classroom responses, hence a reduced class attendance may have been developed as an avoidance strategy. To explore this in more detail a focused study would need to be conducted which could be designed to tease out students' perceptions of the meaning of diagnosis in relation to their dyslexia which might provide evidence that by identifying dyslexia through use of terminology more widely attributed to clinical or medical conditions that are problematic and need a cure, such students perceive their dyslexia in a similar way.

This may be consistent with observations of the day-to-day learning lives of dyslexic students at university conducted in a study by Cameron (2016) which, although might be considered limited due to the case study approach of deeply analysing learning diaries from just 3 research participants, did reveal some relevant points. Notably that in learning situations in which they were attending as members of a class, seminar or lecture in the company of other students, all three participants appeared to find these learning experiences uncomfortable or threatening, reporting 'fear of speaking out in seminars or discussions' so as not to appear 'stupid or incompetent in some way', that they all felt 'different from others', 'less able or intelligent' and that they 'didn't belong' in academic spaces (ibid, 228). All three participants also reported considerable difficulty in verbalising their ideas and thoughts when speaking out in university spaces and how this made them often feel awkward and demoralised. Hence it seems reasonable that students with dyslexia who experienced such difficulties might easily choose to avoid such learning situations where possible. However although this study sharply identifies how some dyslexic students feel when they are learning in the company of their peers, Cameron's study does not mention how these students learned about their dyslexia so we can only surmise that these students are more than likely to have had their dyslexia diagnosed than identified to them in some other way by basing this assumption on the data collected in my study where the majority (60%) of students in my research subgroup of students with dyslexia had their dyslexia communicated to them as a diagnosis rather than in any other way. Cameron's pertinent concluding remarks: 'having the dyslexic label means being constructed by discourses of learning, disability and literacy as an outsider within the education system' and 'there is a justification for some adjustments ... to pedagogy within higher education, (ibid, p235), resonate with the findings above and indeed with the stance of this project. However, evidence is also emerging that many of the competing demands faced by dyslexic students are equally faced by some other contemporary learners. Fraser (2012) suggested that it might be argued in the context of widening participation that many non-dyslexic students from non-traditional educational or socio-economic backgroups also face complex social-learning needs that can impact on their engagement with their studies at university. This point will be explored more fully in the 'Discussion' section of this thesis below (here).

- For the ABC factor, Engagement, although the t-test outcome indicated a difference between the means (for P, and Q+R) that was not significant (p=0.1128) there was nevertheless a small-to-medium effect size, g=0.38 between the mean ABC24-2 values of 52.89 and 45.78 in favour of students whose dyslexia had been disclosed, described or identified to them. Some elements of the factor Engagement are shared with the factor Attendance as shown by the report on the PCA of Academic Behavioural Confidence below, thus it would have been a surprising result had a similar analysis outcome here for the factor Engagement not emerged in comparison with the factor Attendance.

- For Factors 1, Study Efficacy and 3, Academic Output, if considered at the less conventional, 10% level, then the t-test returned significant differences between the ABC Factor means for students whose dyslexia was diagnosed to them in comparison to those whose dyslexia was disclosed, described or identified, ABC24-1: p=0.0875, ABC-3, p=0.0956. In any case, with effect sizes of g=0.41 and g=0.46 respectively, both considered as 'medium', these are indicating an absolute difference between the means that cannot easily be dismissed. Only for the ABC Factor 5, Debating, did the t-test return a notably not significant difference between the means, (p=0.2070), this being supported by an effect size of g=0.26, considered as 'small'.

This analysis indicates that there is a likelihood that the means by which dyslexic students are informed about their dyslexia may be a contributing factor to a measurable impact on their academic behavioural confidence, and hence their academic confidence about approaching their studies at university. It is admitted that with a total sample size of 64 students the sample sizes are small for the subgroups between which differences in mean ABC values have been analysed but given the consistent differences in favour of students who have NOT had their dyslexia diagnosed, the outcome of this analysis does suggest that a further study might be warranted. What seems clear is that the manner in which individuals make sense of their dyslexia and internalize its meaning to them into their academic self-identity is an interesting, relevant and relatively under-researched area, especially in higher education settings. Of particular interest and relevance to the brief analysis above is the research outcome of a study by Thompson et al (2015) which was interested in how adults more generally constructed personal identities and the extent to which these are positioned within discourses of disability or of individual difference. In analysing the themes that emerged from contributions to an online dyslexia support forum, Thompson et al established that significantly, the majority of contributors indicated a greater alliance with the perception of dyslexia as differences in ability than with disability. However of greatest interest was the finding that many felt encumbered by an identity of dyslexia as a disability in educational contexts (ibid, p1328). The authors were able to establish that three distinct identity personae were identifiable: that of being learning-disabled where the dyslexia was focused on impairments and deficits; of being differently-enabled, in which dyslexic individuals were able to focus on their strengths and celebrate their alternative ways of thinking and learning as an asset rather than as a liability, a construction that draws much from the idea that dyslexia is an example of natural neurodiversity, a thesis strongly argued for by Cooper and Pollack amongst others and briefly discussed earlier (here); and finally, a dyslexia-identity construction that was rooted in social-disablement where individuals felt disabled by the ways in which they perceived barriers to be preventing them from conforming to the aspirations of a society which focuses on literacy as a marker of ability, achievement and normality.

Thus the outcomes from this small-scale analysis that has been conducted within this larger study makes a significant contribution to the overall argument being proposed, that a greater effort needs to be made to firstly recognize dyslexia - in whatever ways it can be defined - as a difference rather than as a disability, and secondly that were learning environments designed and structured in a more genuinely inclusive ways, the impact of such learning differences on academic confidence would be further reduced, with the counterpoint that learning quality and hence achievement is likely to be enhanced for students whose learning styles, needs and preferences are atypical.

3. Dyslexia Index

Recall that the research outcomes of this study are heavily reliant on the extent to which the Dyslexia Index Profiler has returned an accurate representation of research participants' levels of dyslexia-ness. This output has been generated by taking as its focus, the range of study skills and learning access, consolidation and synthesis strategies, which are features of how all students engage with their learning at university, rather than by viewing the learning characteristics of dyslexic students through the lens of literacy skills alone. Further recall that the Dyslexia Index Profiler has first determined levels of dyslexia-ness from known dyslexic students and hence used this data to enable Dyslexia Index boundary level criteria to be established. This process has been fundamental to firstly determining whether or not dyslexia, when considered through the lens of academic learning management criteria, can be suggested to have a measurable impact on intrinsic academic confidence; and secondly whether dyslexia-ness can be used as viable discriminator in this non-cognitive context of university study (i.e. not related to academic ability) to identify quasi-dyslexic students from amongst the research group of those who declared no dyslexic learning differences in the research questionnaire. Hence it is necessary to demonstrate as part of this thesis, the comprehensive steps have been taken to firmly establish the Dyslexia Index Profiler as a robust metric for its intended design purpose.

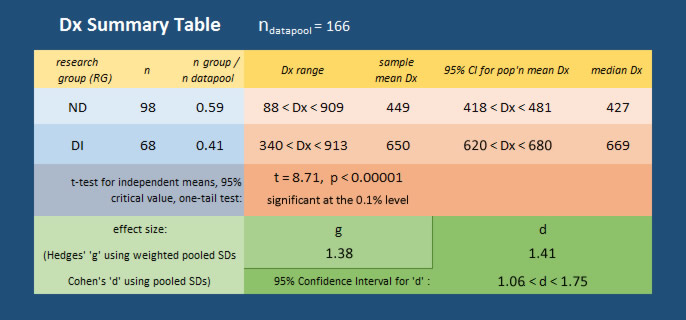

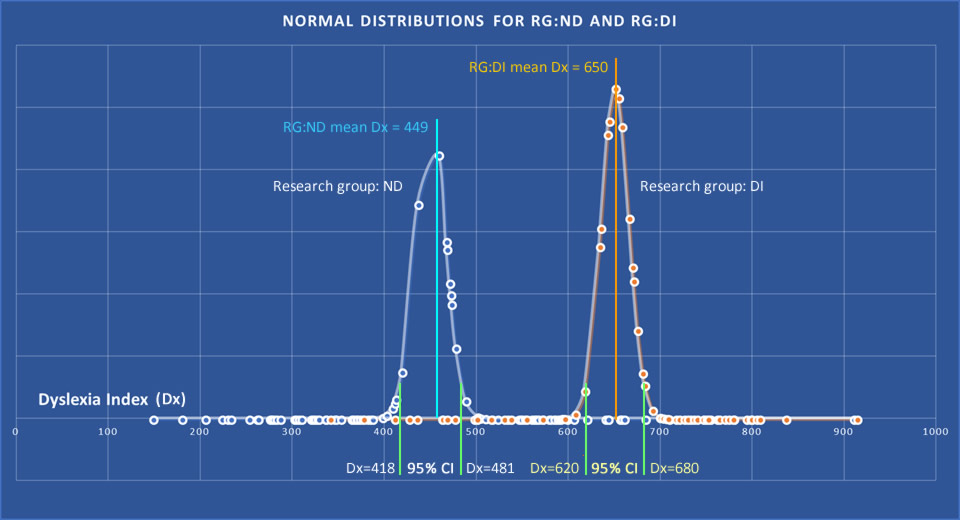

Preliminary analysis outcomes from Dx Profiler data

In total, 183 questionnaire responses were received of which 17 were discarded because they were less than 50% completed or 'spoiled' in some other way. The remaining 166 datasets are collectively referred to as the datapool. Of these 166 good quality datasets, 68 are data collected from students with dyslexia leaving a remainder of 98 datasets from students who indicated no dyslexic learning challenges. The metric Dyslexia Index (Dx) has been used to gauge participants' levels of dyslexia-ness and to establish research subgroups. The table below presents an overview of the distributions of Dx values across the two main research groups, ND and DI, and below that, the distribution curves for the data of both research groups together with the key descriptive summaries of the mean Dx values and the 95% Confidence Interval Estimates for the population means.

It can be seen in Figure 20 that firstly, both groups’ distributions approximate to the typical bell-shaped curve associated with the normal distribution; and secondly that there are marked differences between the Dx values for the two primary research groups, notably:

- both the sample mean Dx and median Dx for the group ND are much lower than for the group DI;

- on close inspection of the normal distribution curves it can be clearly seen the extent to which the upper tail of the curve for research group ND overlaps with the lower tail of research group DI, indicating that there are a significant number of participants in both research groups whose Dyslexia Index values placed them in a mid-range position, approximately 500 < Dx < 600, or to be more specific, in a range that might be considered as between the upper confidence interval limit of RG:ND and the lower limit of RG:DI, that is: 481 < Dx < 620. At least three explanations may account for this:

Nevertheless, displaying the distibutions in this way clearly demonstrates the disparity in levels of Dyslexia Index between the research groups ND and DI.

- there are students in research group DI, who have declared their dyselxia, but whose Dyslexia Index indicates that their dyslexia may have been mis-identified or 'borderline';

- there are students in research group ND who are showing some indications of dyslexia-ness as determined by the criteria of the Dyslexia Index Profiler;

- this variation in both research groups is naturally occuring or contains too small a number of participants for meaningful conclusions to be drawn;

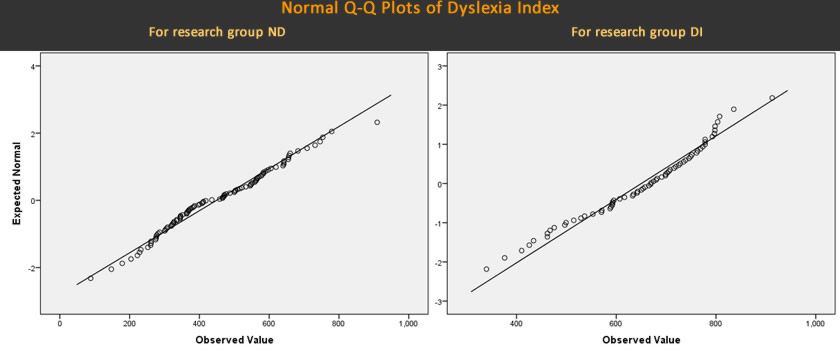

- Student's t-test for a difference between independent sample means was conducted on the complete series of datasets for each group. A one-tail test at the 5% critical value was implemented because the aim was to determing if the sample mean Dx for students who offered no declaration of dyslexia is significantly lower than the sample mean Dx for students who were declaring dyslexia. The Shapiro-Wilk test for normality indicated that both distributions were approximately normal and this test was used in addition to interpretations of Q-Q plots (below). By displaying the datapoints for each research group, ND and DI, given that in both cases these are all positioned approximately along the diagonal, these Q-Q plots also indicate that the distributions are approximately normal. Hence two fundamental assumptions for applying Student's t-test to the distributions is satisfied.

It can be seen from the data table (top) that the resulting value of t = 8.71 generated a 'p' value of < 0.00001 which is indicating greater than a very high a level of significant difference between the mean Dx values. Although Levene's test for homogeneity of variances was violated (p = 0.009), the alternative Welch's t-test, to be used when population variances are estimated to be different, returned the values t = 9.301, p < 0.00001 which is similarly indicating a very highly significant difference between the mean values of Dx.

- The Hedges' 'g' effect size result of g = 1.21 is indicating a large to very large effect size for the difference (Sullivan & Feinn, 2012) in the Dx sample means. Hedges' 'g' is preferred as although it is based on Cohen's 'd', its calculation uses a weighted, pooled standard deviation based which is considered to be better when the sample sizes are not close.

- Cohen's 'd' effect size is also calculated as it is possible to create a confidence interval estimate for this effect size difference between the estimated population means (Cumming, 2010), so together with Hedges' 'g', these are also indicating that there is a strong likelihood of significant differences between the Dyslexia Index of students with reported dyslexia and those without.

These are the expected results and are indicating that the Dyslexia Index Profiler is returning a high Dx value for the majority of students participating in the enquiry who declared their dyslexia and a much lower value for those who declared no dyslexic learning challenge. This outcome indicates that the metric that has been designed for this project as a dyslexia-ness discriminator is generating Dx value outcomes that would be consistent with prior identifications of dyslexia or not. It is of note, and reported elsewhere in this thesis, that in searching for an alternative to existing dyslexia identifiers for use in higher education contexts, Chanock et al (2010) had more confidence in the outcomes from a relatively early self-report questionnaire as a discriminator for dyslexia (Vinegrad's Adult Dyslexia Checklist, 1994) than in the much more involved and formalized York Adult Assessment (Hatcher et al, 2002) which failed to identify a substantial majority of the dyslexic students in Chanock et al's research group as dyslexic. Although there are caveats to their disappointment in the discriminatory performance of the York assessment, their evidence was clearly in support of the benefits of a simple self-report questionnaire which presents a range of typical issues, challenges and difficulties commonly faced by adult dyslexics was clear.

For the research datapool in this enquiry (n=166), it is important to note from the long upper tails to the two confidence interval estimates and normal distribution charts above, that there are a number of participants in the non-dyslexic research group ND who presented significantly higher levels of dyslexia-ness than the majority of their non-dyslexic peers. Indeed, with the upper range limits of distributions for both research groups ND and DI at values within a point or two of each other in the low 900s, this is strongly suggesting that the Dyslexia Index Profiler is identifying students from amongst those who had not declared any dyslexic learning challenges but who appear to be presenting levels of dyslexia-ness in line with the majority of their dyslexic peers. Even taking in account the caveat that the Dyslexia Index Profiler was not built as an assessment or screening tool for dyslexia, this evidence suggests that it could be developed for such a use in higher education contexts, responding to the needs expressed in Chanock et al's paper (ibid) and others who also argue for alternative forms of profile assessment to support students at university who present dyslexia or dyslexia-like characteristics (Casale, 2006, Harkin et al, 2015).

Setting boundary values for Dx

Setting the boundary value for Dyslexia Index in research group ND has been an essential element of the analysis process so that it acts to filter out student responses in this group into the Test subgroup, DNI. As the data analysis process has progressed, a critical evaluation of the setting of boundary values has been applied. Once the data collection period was concluded and all participant questionnaires had been processed, a cursory inspection of the data suggested that setting Dx = 600 as the filter seemed appropriate because the majority of students with declared dyslexia returned a value of Dx > 600. Using this boundary value in research group ND generated a dataset subgroup of n=17 respondents with no previously reported dyslexia but who appeared to be presenting dyslexia-like characteristics according to these high Dx values. By virtue of this boundary value nearly 20% (n=17) of the non-dyslexic students who participated in the research appear to be presenting unidentified dyslexia-like profiles. This is consistent with widely reported research suggesting that the proportion of known dyslexics studying at university is likely to be significantly lower than the true number of students with dyslexia or dyslexia-like study characteristics (Richardson & Wydell, 2003, MacCullagh et al, 2016, Henderson, 2017). Conversely, setting a lower boundary value of Dx = 400 has been essential for establishing the additional comparator subgroup of students from research group ND who are highly unlikely to be presenting unidentified dyslexia - designated research subgroup ND-400, the Base subgroup group. It is considered that this is justified through a similar but 'opposite tail' argument where the majority of students from research group ND who remained in this group after research subgroup DNI had been sifted out, presented a Dyslexia Index of Dx < 400 (n=44, 55%). Only 2 students with declared dyslexia (from research group DI) presented Dx values of Dx < 400.

Research Group Research SubGroup Criteria ND ND-400 students in research group ND who present a Dyslexia Index (Dx) of Dx < 400 - the BASE group; DNI students in research group ND who present a Dyslexia Index of Dx > 600 - this is the group of greatest interest and is the TEST group; DI DI-600 students in research group DI who present a Dyslexia Index of Dx > 600 - this is the CONTROL group;

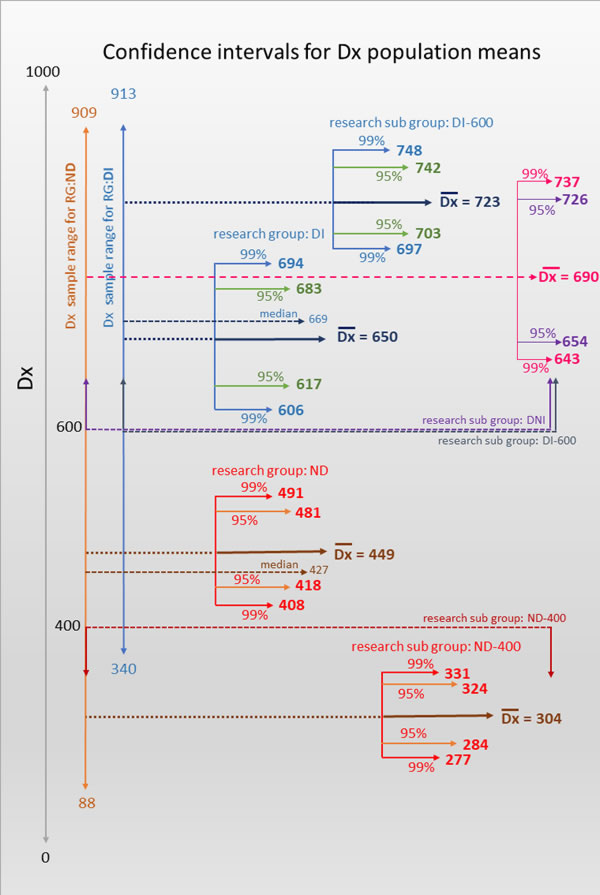

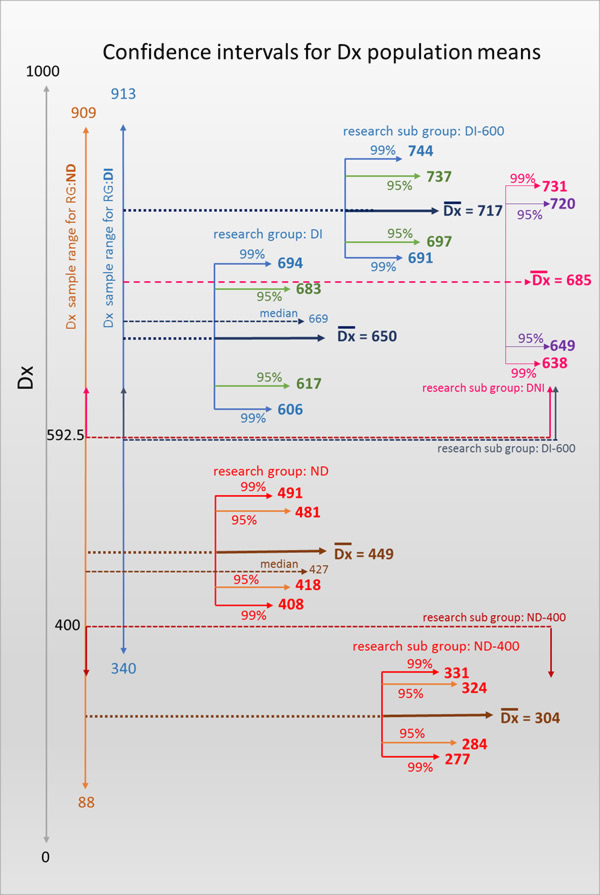

The graphic below supports these boundary value conditions by presenting the basic statistics for each of the research groups and subgroups including confidence interval estimates for the respective population mean Dx values. Thus it is argued that setting Dx filters at Dx = 400 and Dx = 600 was a reasonable starting point for the data sifting process. Note particularly the lower, 99% confidence interval boundary for the population mean Dx for students with identified dyslexia (RG:DI) falls at Dx = 606, and the respective 99% lower CI boundary for students with no previously reported dyslexia falls at Dx = 408, which suggests that the two students with declared dyslexia but whose Dx values fell below Dx = 400 may be safely considered as outliers.

However, in order for the Academic Behavioural Confidence for the subgroups to be justifiably compared, particularly ABC values for the subgroups of students with identified dyslexia from the dyslexic group presenting Dx > 600, (RG:DI-600, this is the Control subgroup) and students presenting dyslexia-like profiles from the non-dyslexic group by virtue their Dyslexia Index values also being Dx > 600, (RG:DNI, this is the Test subgroup) it is important for the key, defining parameter of Dyslexia Index for each of these two subgroups to be close enough so that it can be said, statistically at least, that the mean Dyslexia Index for the two subgroups is the same. Hence, and as can be seen in the graphic above, with research subgroup DNI presenting a mean Dx = 690, some 33 Dx points below the mean for research subgroup DI-600 (mean Dx = 723), it was felt necessary to conduct a t-test for independent sample means to establish whether this sample mean Dx = 690 is significantly different from the sample mean Dx = 723. If not, then the boundary value of Dx = 600 remains a sensible one for sifting respondents into research subgroup DNI, however if there is a significant difference between these sample means then this is suggesting that the two subgroups are not sharing the similar (background population) characteristic of mean Dx and hence comparison analysis of other attributes between these two research subgroups could not be considered so robustly, specifically the subgroups' Academic Behavioural Confidence.

Thus on conducting a Student’s t-test for independent sample means on research subgroups DI-600 and DNI, set at the conventional 5% level and as a one-tail test because it is known that the sample mean for research subgroup DI-600 is higher rather than merely different from that for research subgroup DNI, the outcome returned values of t = 1.6853, p = 0.0486 (calculation source here) indicating that there is a significant difference between the sample means of the two research subgroups, albeit only just. Following several further iterations of the t-test based on selecting different boundary Dx values close to Dx = 600, an outcome that is considered satisfactory has been established using a boundary value of Dx = 592.5. This returned a t-test result of t = 1.6423, p = 0.05275 which now suggests no statistically significant difference between the sample means, although again, this p-value is only just outside the ‘significant’ boundary value of the test.